Risk assessment of migration from packaging materials into food

Yan Zhua, Phuong-Mai Nguyenb, Olivier Vitraca†

aINRA, French National Institute of Agricultural Research, UMR 1145 Ingénierie Procédés Aliments, AgroParisTech, INRA, Université Paris-Saclay, 91300, Massy, France

bLNE, French National Laboratory of Metrology and Testing, 29 Avenue Roger Hennequin, 78197 Trappes Cedex, France

Abstract

This chapter reviews the principles to assess the risk of migration from food packaging materials and related application of such materials. The point of view considered in this chapter is that most of the past crises involving materials could have been avoided with a correct appraisal of mass transfer and the use of numerical tools. Migration modeling is broadly available today and accepted in major global regulations. This chapter does not advertise any platform but shows how their basic or advanced use can prevent the risk of migration regardless of existing or preexisting regulations. Risk assessment is proposed as a generic tool to revise the formulation of materials (thermoplastics, varnishes, coatings, lacquers, inks…), to optimize packaging design and supply chains, to promote new molecular design of additives, to devise improved recycling procedures, to accelerate the acceptation of new polymers and materials (e.g., biosourced, biodegradable, recycled, with repeated use).

Risk assessment of migration from packaging materials into foodAbstract2 Introduction3 What did we learn from crises?3.1 A short history3.2 Why thermodynamics counts3.3 Modern crises4 Risk assessment for decision making4.1 Overview of migration modeling4.1.1 What is currently permitted?4.1.2 Modeling using a tiered approach: from worst-case scenarios to detailed conservative ones4.1.3 Key steps in migration modeling and risk assessment approaches4.2 Migration modeling for compliance testing and beyond4.2.1 Principles of migration modeling4.2.1.2 Migration modeling and similitude properties4.2.1.3 Explicit vs implicit food representation4.2.1.4 Other assumptions4.2.2 Governing equations for monolayer materials4.2.2.1 Overview4.2.2.2 Concentration in the contact phase at thermodynamical equilibrium4.2.2.3 Dimensionless migration kinetics and their analytical approximations4.2.3 Governing equations for multilayers4.2.3.2 Concentration in the contact phase at thermodynamical equilibrium4.2.3.3 Transport equations4.2.3.4 Limiting mass transfer resistance4.2.3.5 Typologies of migration behaviors4.2.3.6 Superposition principles and conservative scenarios for multilayer and multicomponent systems4.2.4 Strategies and equations to simulate multiple steps and conditions 4.2.4.1 Problem formulation4.2.4.2 A first intuitive approach4.2.4.3 Strict conditions of exchangeability with explicit food models 4.2.4.4 Conditions of exchangeability in food implicit models4.2.5 Discussion on the choice of accelerated conditions and the identification of critical steps4.2.5.1 Factors of acceleration and possible biases. 4.2.5.2 Causality, critical steps, and crtical components. 5 Diffusion properties in polymers5.1 Definitions of diffusion coefficients5.1.1 Self- and trace-diffusion coefficients5.1.2 Mutual diffusion coefficients5.2 Effect of the geometry of migrants on $D_p$ values5.3 Effect of the polymer;5.4 Activation of diffusion by temperature6 Sorption properties and partition coefficients6.1 Some definitions6.1.1 Chemical potentials, fugacities, and activities6.1.2 Effective partition coefficients between P and F6.2 Sorption isotherms6.2.1 Linear isotherms6.2.2 Binary Flory isotherms6.2.3 Ternary Flory isotherms6.2.4 Binary Flory-Huggins coefficients in a copolymer AB6.3 High throughput calculations of Flory-Huggins coefficients at atomistic scale6.3.1 Justification and limitations6.3.2 Principles7 Probabilistic modeling of the migration7.1 Beyond intuition7.2 Epistemic uncertainty7.3 Sensitivity analysis of migration models7.3.1 Local sensitivity analysis7.3.2 Global sensitivity analysis via stochastic simulation7.4 Principles of the probabilistic interpretation of mass transfer7.4.1 Input distributions7.4.2 Estimation of probabilities via Monte-Carlo sampling7.4.3 Estimation of joint probabilities via the composition theorem7.4.2 Some illustrations7.4.2.1 Typical probabilistic migration kinetics7.4.2.2 Effect of Bi and sD8 What will be the future?8.1 Extending the legal scope of migration modeling8.2 Extending the capacity of migration modeling8.3 Bridging migration modeling, safe-by-design, and ecodesign approaches8.4 Online resources ease risk assessment8.4.1 Lower bounds of toxicological thresholds for non-evaluated substances8.4.2 Migration modeling tools9 References

2 Introduction

What is migration?

Migration is a general term for spontaneous mass transfer of chemical substances, and, in the context of food packaging, it indicates an extraction of packaging constituents and their transfer to the food. Industry and authorities recognized the fate of cross mass transfer between materials and the resulting contamination of the food evenly. The term migration was consequently preferred to the contamination one in the scientific literature and legal documents. During the last decades, the concern about the safety of food contact materials (FCM) raised with our appetite for transformed food and ready to eat meals, and with our always growing needs for disposable packaging. Nowadays, FCM is identified as the prevalent source of exogenous chemical contaminants in food, ahead of pesticides, veterinary drug residues and other environmental contaminants . The ubiquitous contamination issue was thought to be restrained initially to contact layers and materials, but it is far from being the case. Modern food packaging systems are, indeed, printed, coated, laminated and associated with other materials. The whole history of these materials must be considered, as they may have been subjected to repeated use, brought to a second life via a recycling process, stored in reels or stacks contacting internal and external surfaces; shipped with other materials during long and warm periods. The whole contamination problem can be envisioned as a cross mass transfer of several substances between Matryoshka or nesting dolls. The pre-weighted food feeds the smallest doll and is surrounded by many layers including the rigid walls of the primary packaging, a sleeve, the transport cardboard box containing several sale units, the treated wood pallet, a wrap cling film, etc. until the freight container. In ready to eat meals and convenience foods, additional components may be present internally such as a bag preventing direct contact with walls, individual packages or wraps for portion control, separators and specific holders, sachets for seasonings, active elements to increase food shelf-life, etc. The whole picture is not complete without citing the many tie layers, the glued labels, the printed and coated surfaces. The ultravacuum and aerospace industry would have regarded similar materials and combinations as a substantial reservoir of organic compounds without exception. As an illustration, the NASA compiled more than 35,000 outgassing data 1, for almost any material, which could enter in a spacecraft, including many commodity materials such as thermoplastics, coatings, and tapes.

Our approach to risk assessment

This chapter provides a comprehensive description of molecular processes responsible for the migration of packaging constituents and their pathways to the food with or without direct contact. The recurring structure of contamination scenarios leading to the past major crises is discussed and analyzed regardless of the modalities of their regulations. The distance between the facts and practices is maintained all along this chapter, as the regulations and the good manufacturing practices follow the crises and rarely precede them. Major regulations (the US, European and Chinese) are sketched to highlight their convergence on the use of modeling to demonstrate compliance and to evaluate the safety of recycled materials. The miscalculation of the connection between chemical structure and physicochemical properties (volatility, solubility, diffusivity) has been the foremost cause of past crises. Computer and proper simulation procedures can assist efficiently small and intermediate industries in overcoming internal knowledge limitations on materials, mass transfer, and physical-chemistry. By comparing with acceptable thresholds, migration modeling can be extended at low cost to non-evaluated and non-intentionally added substances. In the foreseeable future, similar techniques might be used to tackle the diffuse risks raised by endocrine-disrupting chemicals 3, 4 alone or in mixing cocktails 5. More globally, the extension of predictive tools and approaches will benefit not only the evaluation of the contribution of food contact materials to the global exposome 6, but it will also facilitate the adoption of preventive approaches all along the supply chain. Safe-by-design approaches, including additive redesign, optimization of the formulations (choice of substances and amounts), new packaging design and good manufacturing practices, will reduce the risk of unintended food packaging-interactions 7, 8. Improving the way food ingredients are stored and processed will bring additional risk reduction, beyond the reduction of the migration in the finished product.

The scope of migration modeling

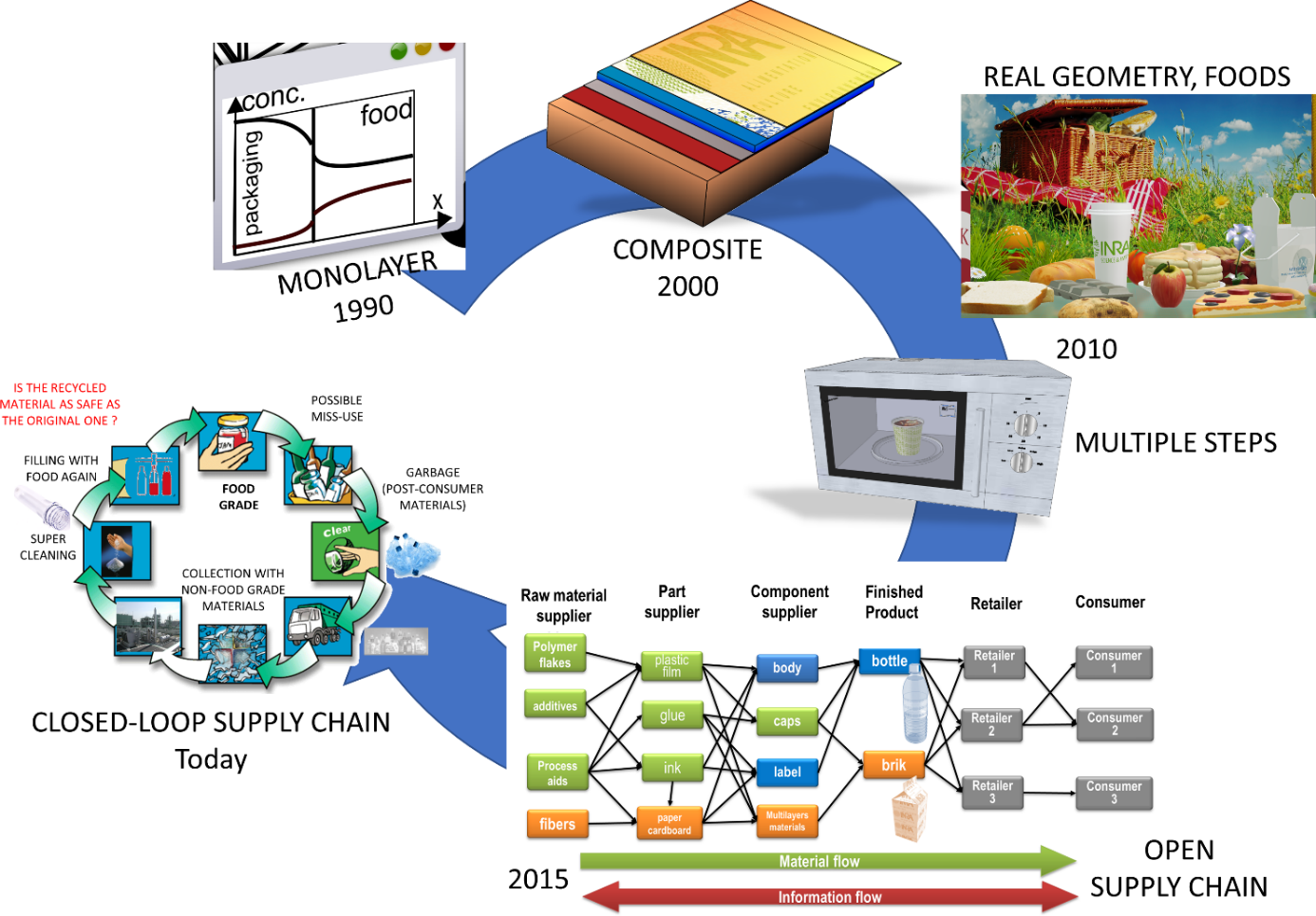

The scope of migration modeling has been underestimated in the past and limited to compliance testing under worst-case scenarios. The uncertainty and the pioneered methods were too coarse thirty years ago. We suggest that the scope can be broadly extended today as shown in Figure 1. Earlier models could cover only single materials, simple geometries without any dynamic change of conditions. The most advanced models can today incorporate information at molecular scale and cover an entire supply chain. The chapter focuses on the key details and features required to get robust modeling of migration at the scale of a material, component (label, cap…), of an entire food packaging, of industrial practices. The methodology to get estimates of consumer exposure are not covered in this chapter because they are directly related to the design of the packaging itself.

Figure 1. Evolution of the scope of migration modeling during the last decades

Beyond migration modeling: a holistic science

Once used, the packaging losses all its value, but its cost remains high for the environment. Revised versions of life-cycle-analysis propose to add chronic effects on health due to long-term impacts on the environment9-11. We promote this initiative for applications in food contact but also for cosmetics, pharmaceutical, medical, biotechnological ones and for any situation where the release of chemicals by materials is of concern (e.g., occupational exposure). Innovations could come shortly at the cost of a full revisitation of our engineering practices. A global science needs to emerge beyond common mistaken beliefs: migration can be avoided, biosourced materials are safer, biodegradable as recycled materials can be used without a safety assessment. We do not pretend to cope with all problems, but we suggest thoughtful routes to evaluate the risks of contamination at any stage of the supply chain and consequently to measure the benefits of alternative solutions. From step to step, we could approach better inertia as it has been achieved to minimize outgassing in ultravacuum systems.

3 What did we learn from crises?

Highlights on crises associated with food contact materials

- The contamination of food by materials in contact is never fortuitous, but it may be not avoidable.

- Only the nature of the migrating substances, the extent of the migration can be controlled by our choices.

- Most of all crises if not all could have been predicted with relatively simple descriptions of mass transfer phenomena and thermodynamics.

- As a corollary, consumer exposure to substances from food contact materials could be reduced.

3.1 A short history

Crises tend to predate regulations and frequently them — we coin crisis a situation where food safety is seriously questioned due to systematic contamination by one or several FCM. The contamination was usually unexpected but not unforeseeable due to its anthropogenic nature. Comparatively to food infection and food intoxication, the possibility of crises by FCM substances has been recognized lately in Europe. The obligation of traceability of all packaging components to organize the recall of packaged food products were implemented only in 2004 through the framework regulation 2035/2004/EC.

Thirty years ago, western governments endorsed enthusiastically an early idea hypothesized by Jerome Nriagu 12 and popularized by Clair Patterson 13, whereby Roman civilization collapsed as a result of lead poisoning. “Although today lead is no longer seen as the prime culprit of Rome’s demise” (quoting 14), lead poisoning from leaded pottery and earthenware was known for centuries. All possible sources of lead were individually tracked by authorities in the nineteenth century, in particular, after the development of wrought-iron canisters. The French ordinance of March 21th, 1879 (see p 231 of 15) prohibited, for instance, the use alloys of tin and lead for all inner parts including welding. The French regulation of 1908 was even more explicit “no food substance should contain any harmful product or chemical substance” 16. In modern times, the editorial of the New England Journal of Medicine was heading in 1972 “The invisible pollution” 17 after the discovery of plasticizers in human blood stored in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) bags 18, 19. Similar contaminations were associated with tubbing used for culture tissues 20. The exact nature of the contamination mechanism was not fully established at the time, and an analogy with the corrosion of metallic materials was falsely suggested 21. The first mechanistic review of what called “extractivity” or “migration propensity” appeared only in 1980 22, 23. Three mechanisms of contamination were listed:

- contamination only from the extreme surface of the material in contact;

- the diffusion-controlled release of the material in contact;

- penetration of the polymer matrix by the contacting phase (liquid) and subsequent extraction of materials constituents.

Early descriptions were strongly influenced by the behavior and the dominance of PVC in the seventies and eighties, and by the lack of sensitivity of contemporaneous analytical techniques. In spite of erratic results and difficulties in getting reproducible kinetics, the corollary reasoning supported the confidence of stakeholders in the apparent inertia of thermoplastics and thermosets lastingly. It was falsely thought that:

- the absence of direct or permanent contact,

- aqueous contact,

- high molecular weight additive or residues,

- low temperatures

would prevent any significant migration and do not need proper attention. At the time, only a study using radio-labeled additives 24-27 carried out under contract for the Food and Drug Administration and, subsequently, interpreted in detail during the Ph.D. thesis of Thomas P. Gandek at MIT 28 highlighted several abnormalities, which were anticipating future crises. In poor barrier polymers, the hydrodynamic conditions in the contacting liquid were showed to control the release; but neglecting it them was not underestimating migration, on the contrary. In aqueous food simulants and presumably in any aqueous-type food, the decomposition of additives displaces continuous the apparent thermodynamical equilibrium between the material and the liquid in contact. Contrary to previous descriptions, the contamination was found unbounded 29, 30.

Similar conclusions were found for large additives migrating to dry food simulants for short periods at temperatures elevated but sufficiently close to those met during transportation 27. The most outstanding finding was that the migration rate could not be overestimated by experiments using corn oil. Accelerating testing using food-simulating liquids is a common practice to evaluate the risk of migration, but it was emphasized that more rationale was required for evaluating with sufficient confidence the risk of migration for new polymers. Simulating liquids should be chosen respectively to the nature of both the migrating substance and of the original polymer. Fatty food simulants offer worst-case migration and extraction capabilities only for hydrophobic substances in apolar polymers. Aqueous simulants are more aggressive for polar or charged substances, and polar polymers 31. Since most of the food products are multicomponent and multiphasic (e.g., emulsions, gels, cake with chocolate, etc.), they cannot be reduced easily to a single contact phase when different classes of migrants are involved.

3.2 Why thermodynamics counts

Thermodynamics has been praised by the whole packaging community, including the chemical, compounding, processing, recycling and food industries, as well as authorities and safety agencies. It has been regularly as the primary argument to justify the conditions of compliance testing (choice of simulant, test temperature and contact time, extrapolation rules and migration calculations) and to authorize recycling process of polymers, active packaging, etc. A naïve reasoning may, however, lead to severe consequences, which should be underestimated. A common mistake is to assume that mass transfer stops after some long time. The transferred amount is assumed to reach, indeed, a maximum controlled by the partition coefficient between the packaging and the food. Statistic mechanics teaches us that this macroscopic description is oversimplified and proceeds with an analogy between a mechanical equilibrium and a chemical equilibrium. At molecular scale, all the substances continue to move freely at equilibrium as they were moving before the whole packaging-food system reaches a macroscopic equilibrium. In a closed system, the equilibrium is associated to a zero net mass balance across the packaging-food interface: the number of molecules of type A entering in the food is exactly compensated by the number of molecules of type A leaving the food. We might think that because the food has a larger volume than the packaging, the return of molecules is unlikely. It is however not correct because the substances are transported faster in food than in dense polymer matrices. Only when the volume ratio food-to-packaging becomes very large, the probability of return approaches zero and a total extraction of A is expected regardless of its affinity for the food.

When a chemical reaction transforms the species A into the species B in the food, the previous balance is profoundly modified, and more substances A are invading the food than substances A returning to the packaging. Similarly, when the substance A cleaves into two breakdown products and in the packaging, parts of substances A that migrated in the food are partly reabsorbed by the packaging itself. When the reaction is almost complete, only traces can be identified in the food. On the opposite, substances and can migrate (faster than A) and may remain undetected if not specifically targeted.

Adding more packaging components (several layers, cap, label, etc.), variable temperatures and complex contact conditions complicate the mass transfer description, but thermodynamics always provides the relationships to encompass all possibilities of exchanges including in multiphasic foods. The thermodynamics needed is not equilibrium thermodynamics, as it ignores the time-course of the migration processes, but a local version, where equilibrium is reached only at the interface between each phase and component. The classical non-equilibrium thermodynamical concept of local thermodynamic equilibrium is robust enough to integrate non-linear sorption isotherms, coupled mass transfer and plasticizing effects. When the relaxation of polymer systems is longer than the timescale of mass transfer (e.g. , in glassy materials, hysteresis effects), constitutive equations need to be modified to integrate the mechanical behavior of the materials (swelling or densification).

No food packaging system is enough isolated from the rest of the world so that a true thermodynamical equilibrium cannot be finally observed literally in real-life systems. Preventing the loss with surroundings in tests and calculations maximizes the amount transferred to the food. Conversely, not considering the possibility of redistribution of migrants between materials during their lifetimes hampers the proper management of non-intentionally added substances.

In shorts, most of the experimental evidence supporting regulation and rules were obtained on simple materials, preferably monolayer and apolar ones at rubber state. Equilibrium was reached rapidly in conditions accelerated comparatively to the real shelf-life of food products. In this case and only in this case, the concentration in the simulating liquid increases monotonously with time.

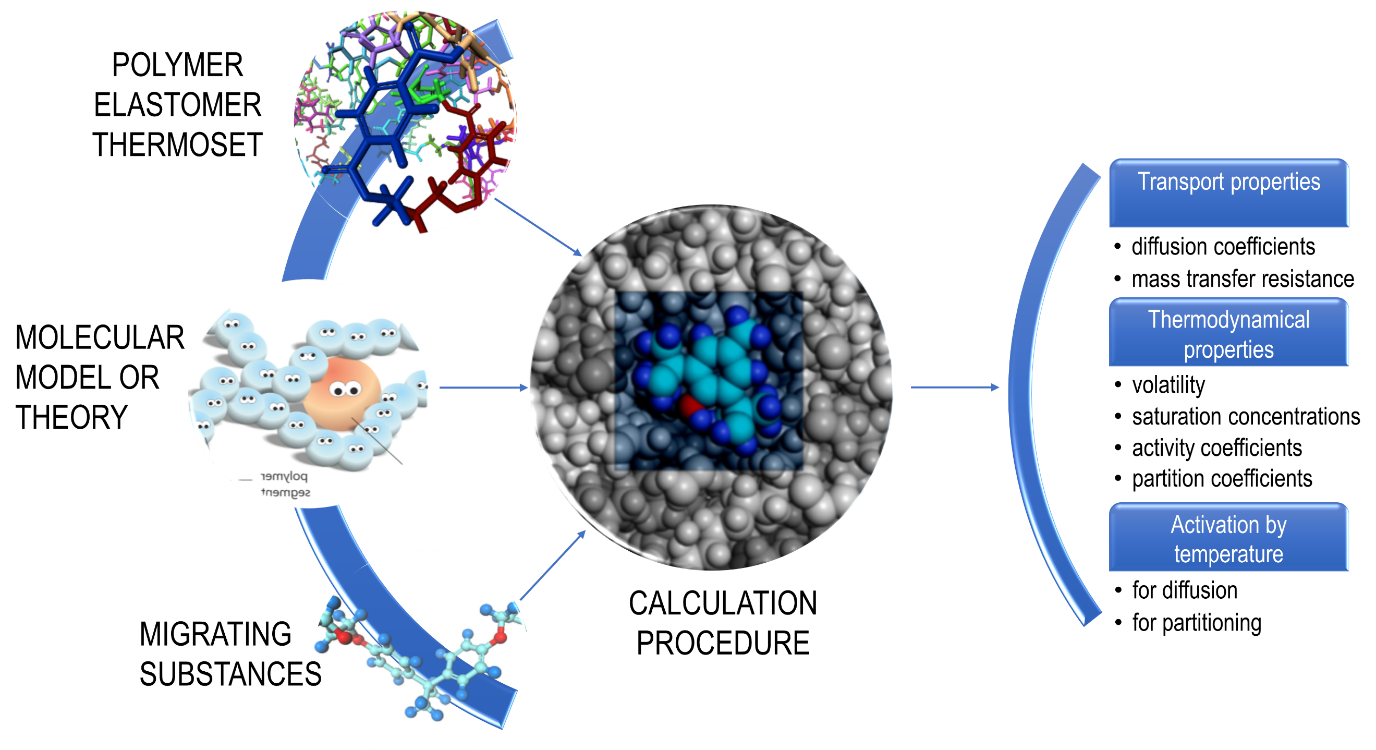

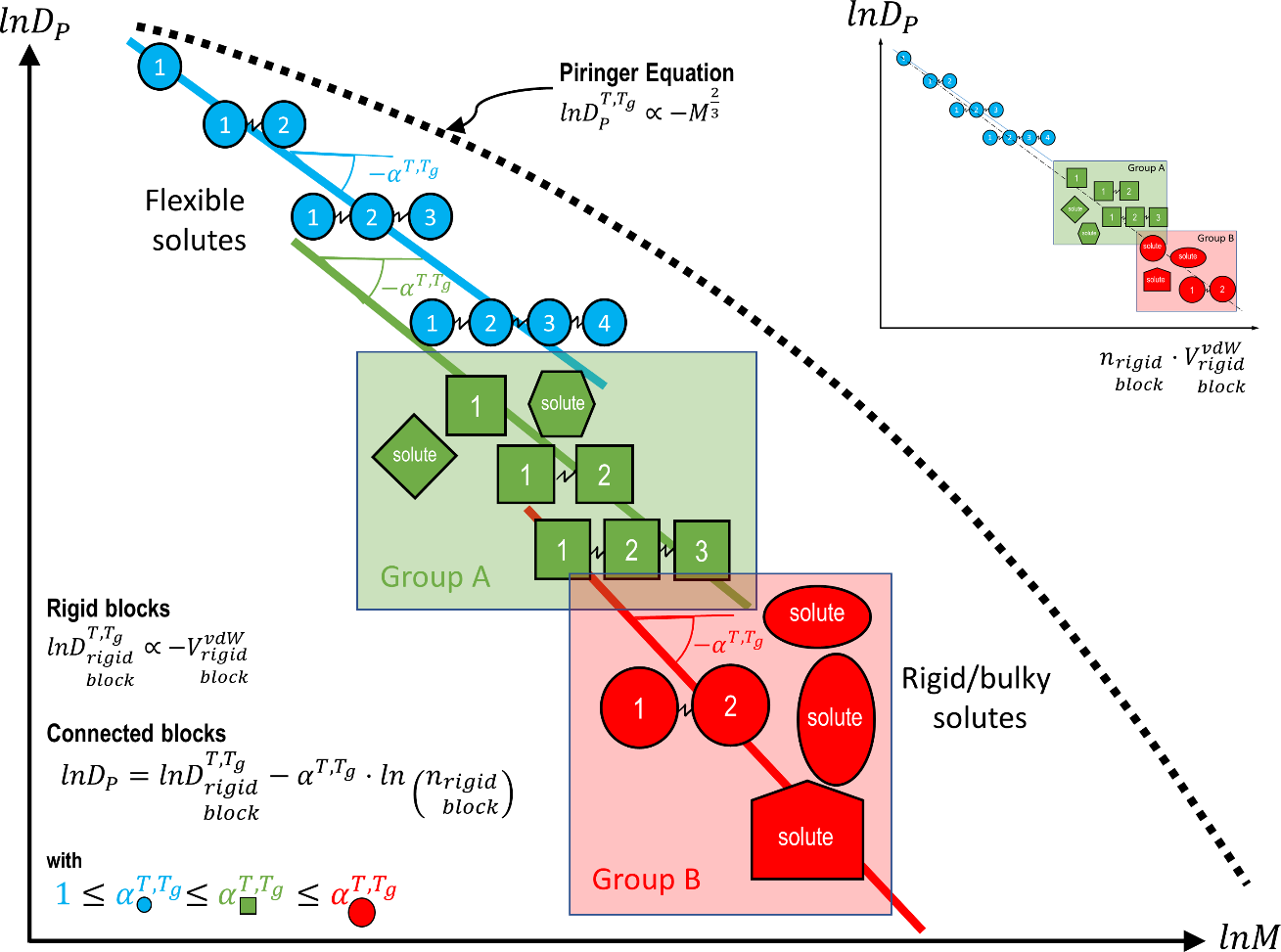

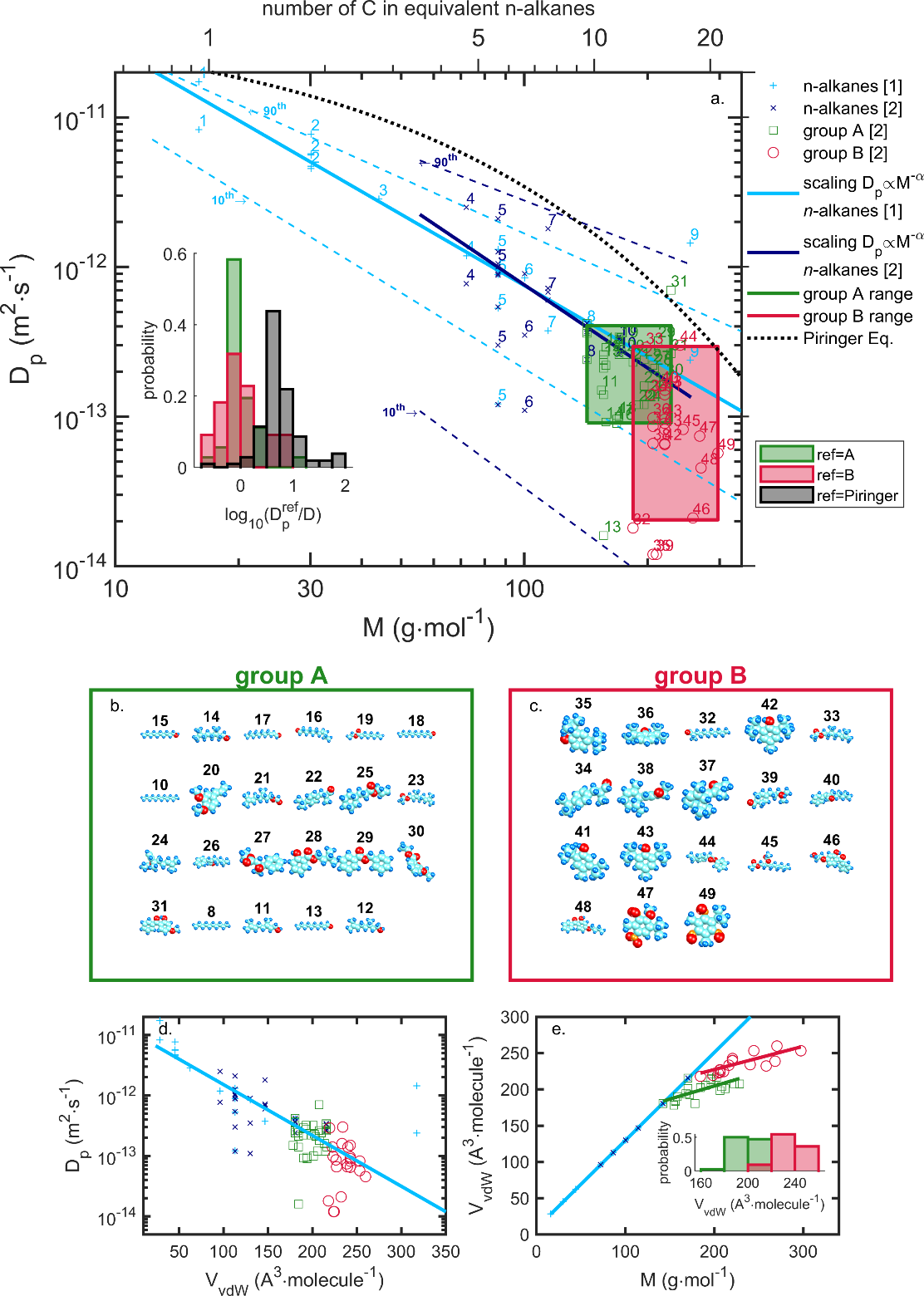

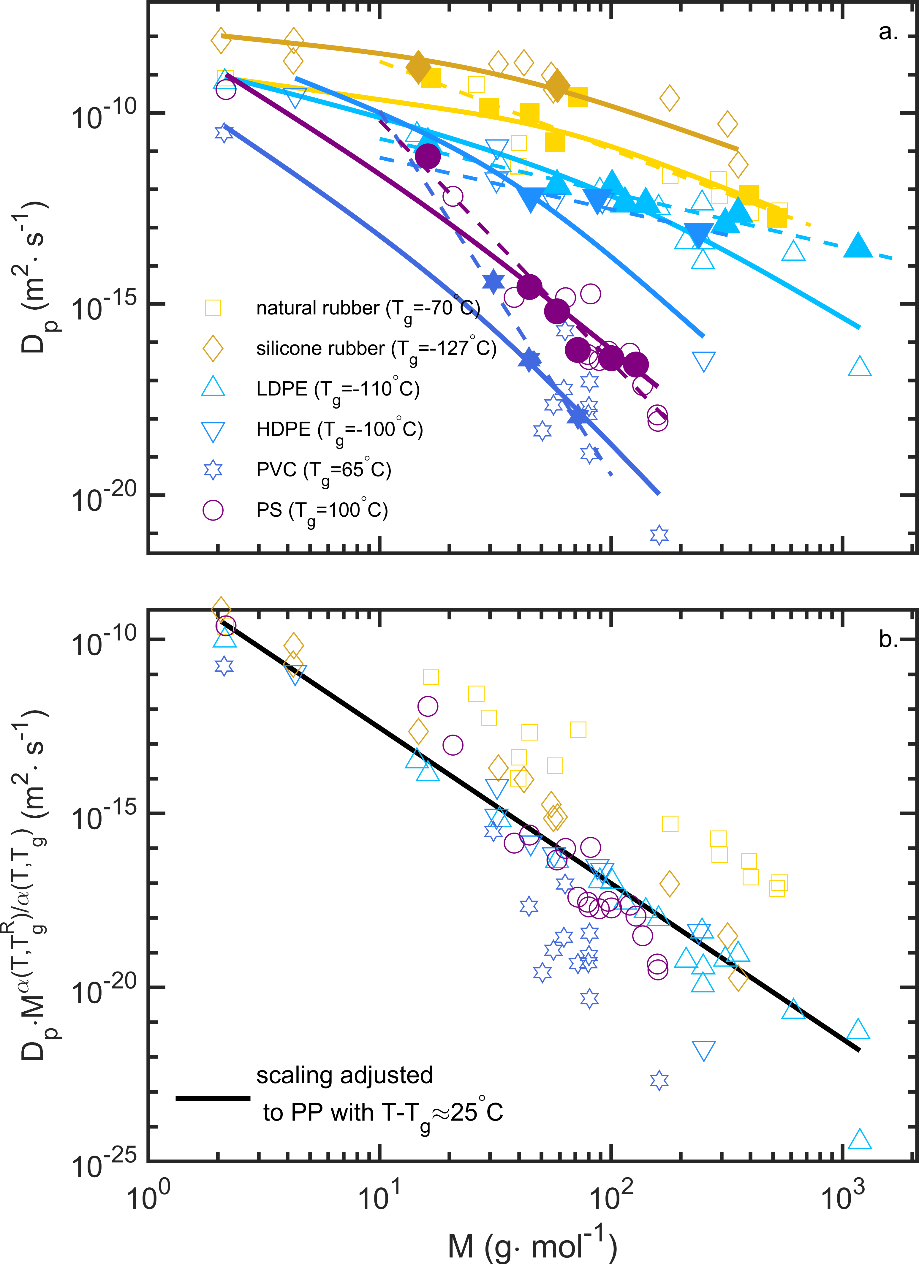

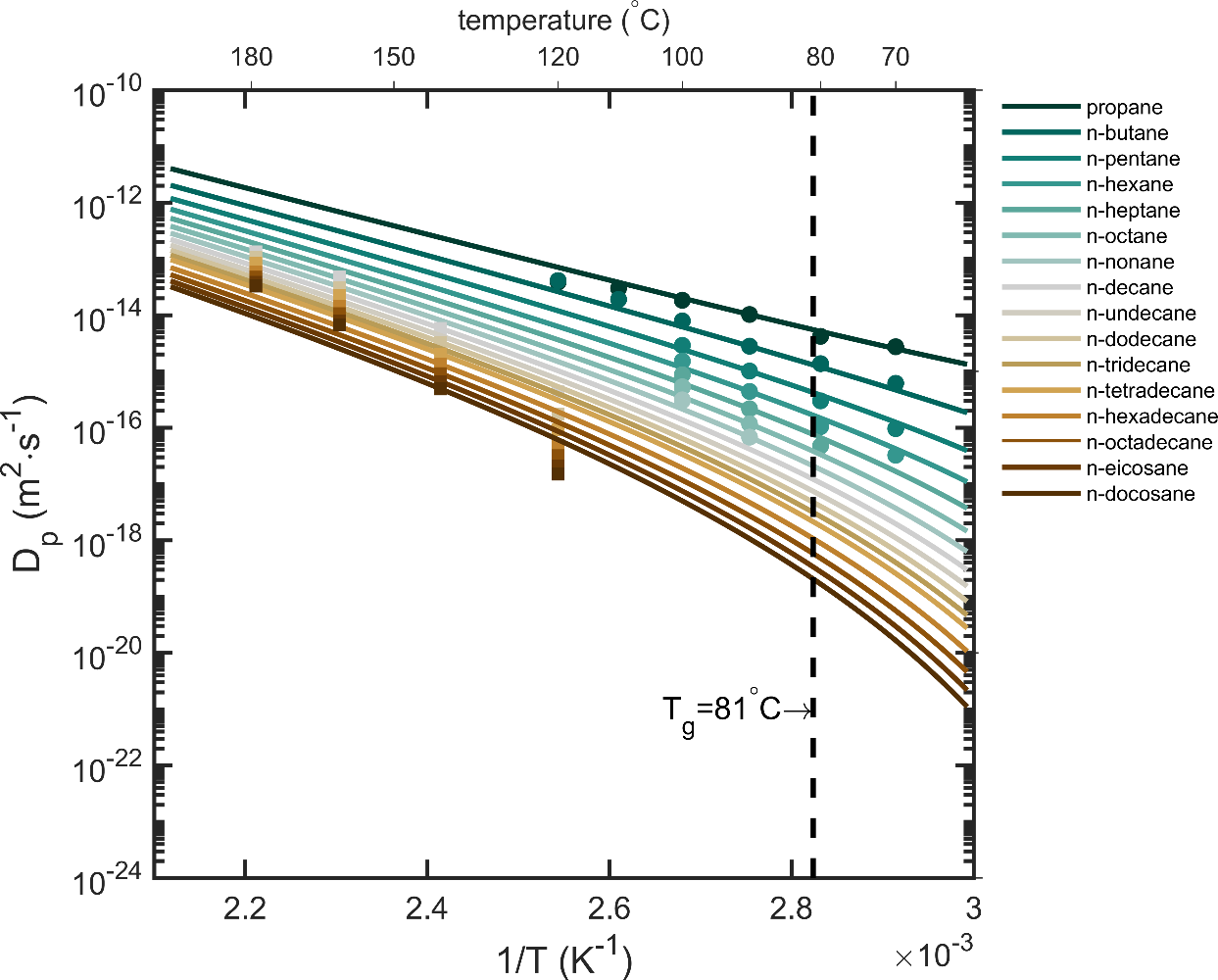

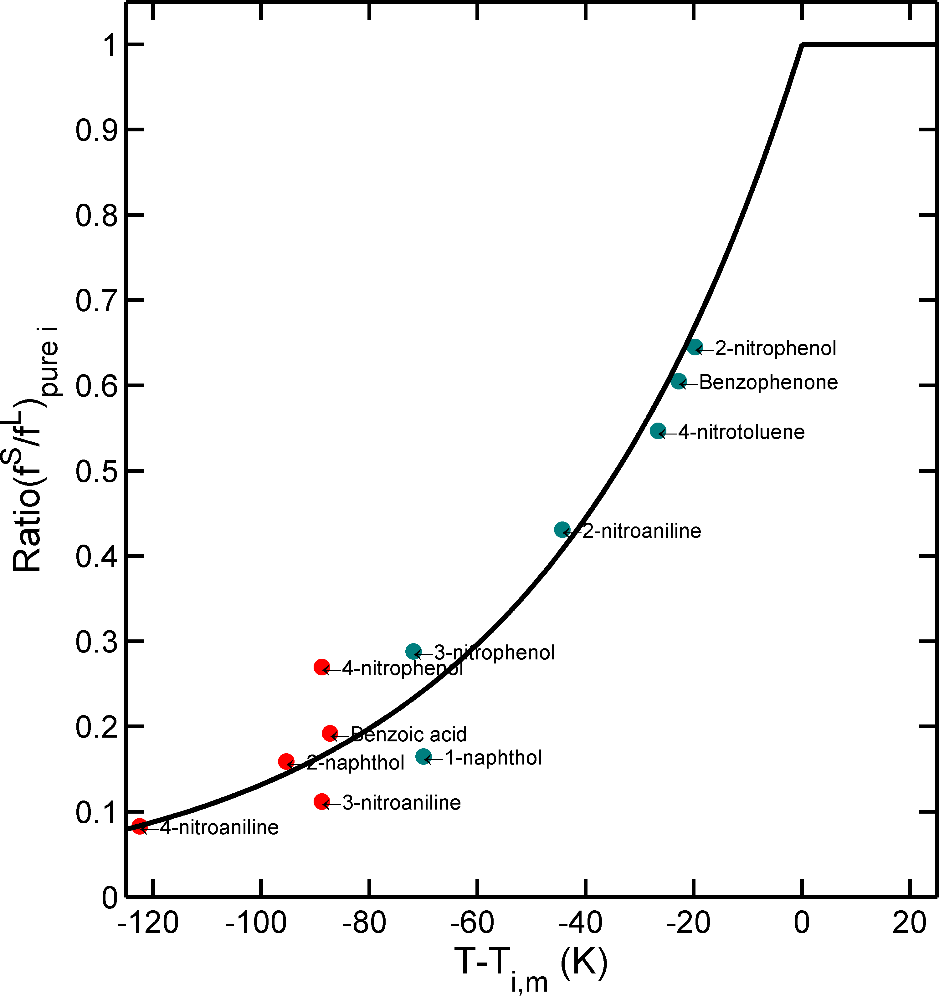

Thermodynamics offer a robust framework to address all previous issues at the scales of molecules, where the interactions and the macroscopic properties emerge from the vibration of atoms. Theories or robust inference rules have been developed to relate the chemical structure of the migrants and the polymers to the diffusion and partition coefficients, without requiring an explicit description of molecular interactions. The principles of quantitative structure-relationships detailed in this chapter are sketched in Figure 2. They should not be considered as definitive rules, but as an ongoing process, where updates are regularly obtained.

Figure 2. Principles of quantitative structure relationships to predict common transport and thermodynamic properties needed for migration modeling.

3.3 Modern crises

“Early civilizations adopted laws that punished sellers of tainted food” as quoted by Merill 32, In 1958, the US Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act introduced the Delauney clause, which prohibits the use of any substance as food additive “if it is found to induce a cancer when ingestion by man or animal” 33. In the US regulation system, the concept of additives is broad and comprises substances, which may become a component of food or otherwise may affect the food characteristics 34. They include therefore any substance released by food packaging, regardless of the nature of the materials. As a result, it is the responsibility of the industry to submit a dossier to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to get a new substance, a new polymer and new application of packaging approved. Similar rules were enforced successively in EU via the directive 1990/128/EEC 35, the regulations 2002/72/EC 36 and 10/2011/EC 37. The dossiers apply, however, only to initial substances of plastic materials monomers and additives. China adopted recently legal requirements close to the European system for plastics with a premarket approval for both the plastic resins and the additives 38. The inventories of substances are compared in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of the Inventories of food contact substances in US, EU and China. Sources 37-39

| MATERIALS | US regulation39 | EU regulation and provision | Chinese regulation38 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plastics, resins, additives, polymerization aids | 1340 food contact notifications + GRAS and prior sanctioned substances (Title 21 CFR Parts 175, 177, 178) | 843 in the EU positive list37 including 428 with SML or SML group, and 587 additives | 339 in positive list 86 with SML/QM or SML group |

| Rubber | 176 substances in the French positive list 40 | 88 substances 23 with SML/QM | |

| Printing inks | 5104 substances (IAS) in EuPIA guidance41 and Swiss Ordinance42. For NIAS, see43 | 97 substances 33 with SML/QM | |

| Paper and board (including recycled) | 482 substances (Title 21 CFR Part 176) | 1556 substances additives in Council of Europe resolutions 44 and good manufacturing practices 45. For recycled materials, see 46, 47 | 277 substances 77 with SML/QM |

| Compliance testing by modeling | Yes (plastics) | Yes (restricted to plastics) | No restriction on applicable materials |

| Risk Assessment including migration modeling | Broad range of applications in petitions in relation with consumer exposure determination | Broad range of applications in petitions in relation with an upper estimation of consumer exposure | Not applicable in petitions |

GRAS = generally recognized as safe; SML: specific migration limit (maximum concentration in food); QM: quantity maximum (maximum amount in the material before contact); IAS: intentionally added substances; NIAS: non-intentionally added substances.

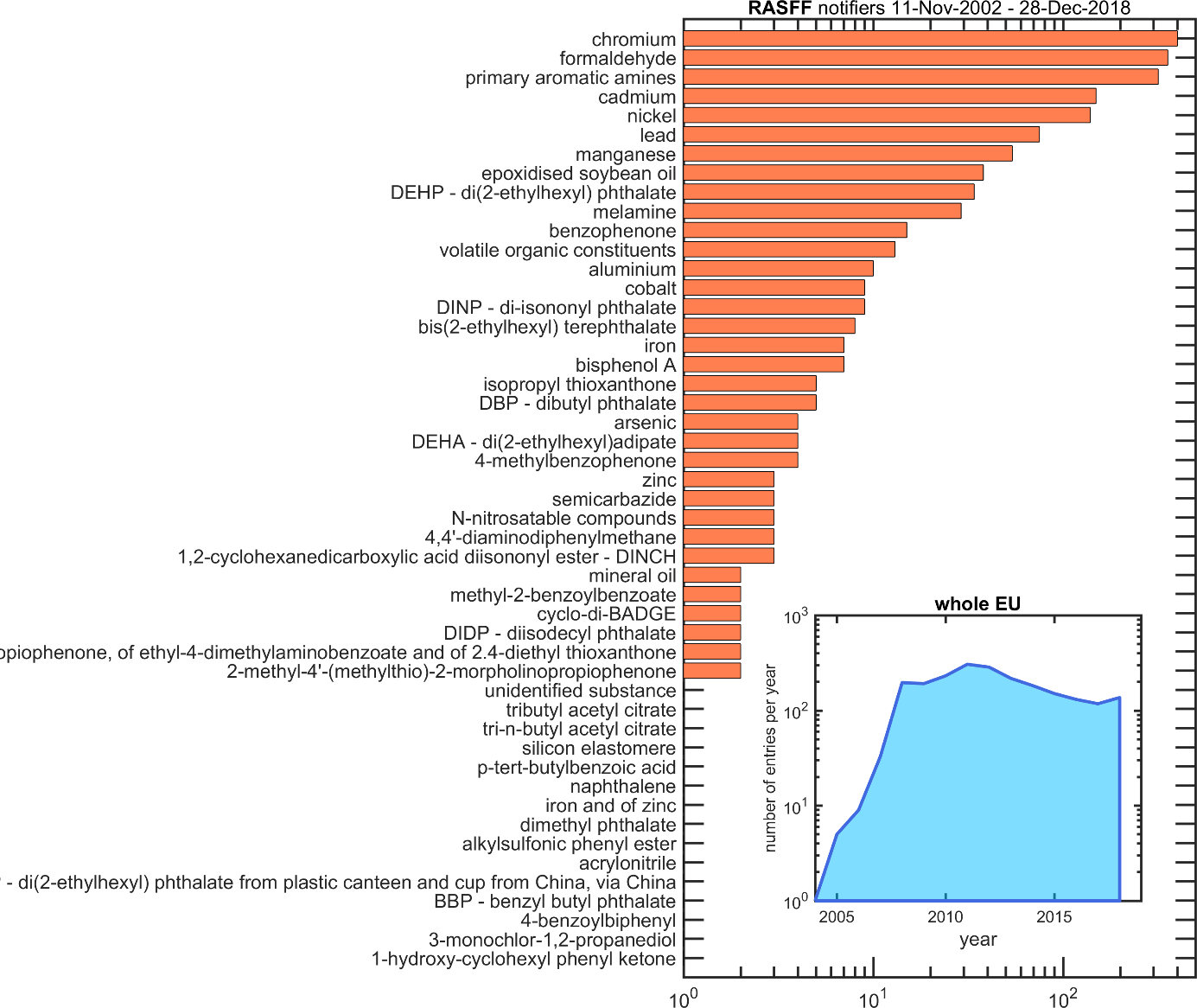

A crisis occurs when a substance not authorized is found in the packaging material or when the levels in food raise concern due to its ubiquitous distribution or due to significant exposure of specific or global populations. As an illustration, the substances from materials intended to be in contact with food and exceeding EU migration tolerances during the period 2002-2018 are listed in Figure 3 in decreasing order of occurrence. Half of the 1956 cases are associated with imported tableware and with contaminations by heavy metals. Packaging alone represent less than 6% of the total with lids involved in 45% of cases. The main crises associated with packaging materials and their likely causes and consequences are reviewed in Table 2.

Table 2. Analysis of the major crisis involving food contact materials

| Crisis (class) | Period (key references) | Cause | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levels of plasticizers from PVC cling films above 100 mg**⋅kg-1** | 198x 48-53 | Widely used as additives (plasticizer, solvent) with large amounts, not covalently bonded to the material backbone | Restrictions or ban of many phthalates in FCM applications |

| High levels BADGE and of its reaction products of BADGE from can coatings | 1997-today 54 | starting substance for the manufacture of epoxy resins, used as an additive, functioning as a stabilizer and as a plasticizer à reaction with medium in contact | TDI 0.15 mg/kg b.w (BADGE) SML 1 mg/kg of food (reaction products) |

| Primary aromatic amines from agglomerated cork stoppers | 2000-today 55, 56 | Surface treatment, adhesive, lubricant à reaction products | SML 0.01 mg:kg of food applied to the sum of PAA released (annex II of 37) |

| Primary aromatic amines from laminates | 2000-today 57-59 | polyurethane adhesive à reaction due to thermal treatment | SML 0.01 mg/kg of food applied to the sum of PAA released (annex II of 37) |

| High levels of epoxidized soybean oils | 1988 – today 60 | Large amounts in PVC plasticized, high lipid solubility, long time storage | Lowering of SML to 30 mg/kg for infant food |

| High levels Nonyl-phenols | 2004-today 61 | Breakdown product of tris(nonylphenyl)phosphite (authorized in EU 10/2011) | strictly limited by Directive 2003/53/EC 62 restriction REACH annex XVII 63 |

| Semicarbazide leached from the thermal decomposition of azodicarboamide from gaskets used in baby food jar closure technology (press twist and twist-off lids) | 2003-2005 64, 65 | Breakdown product of azodicarbonamide during the heat treatment | ban 66 |

| ITX | 2005-today 67 | Bad identification of transfer/contamination paths from ink to foodstuffs Bad information exchange between stakeholders in supply chain | No regulated in plastic material regulation REACH study |

| Benzophenones from printing inks | 1995-today 68 | Bad identification of transfer/contamination paths Bad information exchange between stakeholders in supply chain | SML: 0.6 mg/kg |

| Bisphenol A leached from Baby Bottles | 2004-today 69, 70 | Widely used in infant products | Lowering of SML to 0.05 mg/kg Replaced by other substances New risk assessment ongoing by EFSA |

| Ubiquitous contamination by mineral oils from recycled papers and boards | 1993-today 71, 72 | Recycled paperboard, difficult in analytical analysis | Proposition of SML of 0.5 mg/kg |

The inset of Figure 3 and Table 2 would suggest that the number of contamination cases would increase with time. The better effort of authorities to identify, track and contain the contamination by FCM led to more frequent reporting. Regardless of the real risks, the successive crises can coatings, bisphenol A and mineral oils increased the awareness of the general population and, in return, promoted the sake of different management strategies and better integration along the supply chain.

Figure 3. List of contaminants from food contact materials reported in the European Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed73 (extraction on Dec 31st, 2018). The inset shows the evolution with time of the number of alerts issued by all member states, corresponding during the period 2002-2018 to 955 border rejections, 459 alerts, 288 information for attention, 284 information and 216 information for follow-up.

4 Risk assessment for decision making

Highlights on modeling, risk assessment, and decision making

- Migration modeling is a cognitive process aiming at capturing the essential mass transfer phenomena responsible for the contamination of food by substances originating from materials.

- Calculations are carried out in a way that they guarantee they are more severe than real conditions.

- Only compliance can be demonstrated by calculations and simulations.

- Calculations are in essence different than accelerated tests and should be used to reproduce real but conservative contact conditions (time, temperature, interactions with food).

- Sophistications in calculations require to be introduced progressively and in a comprehensive manner starting from the most conservative (severe) conditions.

- Variability and uncertainty must be characterized and documented.

- The whole process can be integrated into preventive approaches (safe-by-design) or stochastic calculations (see section 7)

4.1 Overview of migration modeling

4.1.1 What is currently permitted?

Notwithstanding the introduction of accelerated tests for compliance testing, simplified alternatives to traditional migration testing were sought in the nineties. The common interests of the industry and the authorities were summarized by Begley 74, “Traditionally, migration tests are performed by using food-simulating liquids such as water, edible oils, ethanol/water solutions and sometimes food. These tests are time-consuming in two ways; generally, the accelerated tests run for at least ten days, and the analysis of the migrants at low concentrations in the simulants or food is generally difficult. These analyses are also expensive and generate hazardous laboratory waste”. Migration modeling was proposed both in the US (earlier works 75 ) and in EU (earlier works 76-79) to tailor the process of migration assessment. Migration modeling is nowadays mostly extended in EU via a specific task force TF-MATHMOD publishing updated guidance 80 Migration modeling is broadly accepted for compliance testing 37 and risk assessment (see 81) of food contact materials with the following strict restrictions:

- estimated values – whatever the calculation procedure and underlying assumptions – must be at least as severe as the real test and overestimate the migration;

- calculations cannot be used to demonstrate the non-compliance.

Similar methodologies are used by the industry to calculate the level of decontamination (cleaning) of materials in mechanical recycling processes. But in this case, the amount released by the material should be estimated accurately and not overestimated. Additionally, it is worth noticing that the state of polymers is very different between the conditions met by the consumer (moderated temperatures) and the industrial conditions of recycling (high temperature, solvent-swollen). Only mechanistic modeling can cover both cases. Modeling is not restricted to any material (thermoplastic, thermoset, paper, and board), but it has been tested chiefly for thermoplastics and with non-uniform coverage.

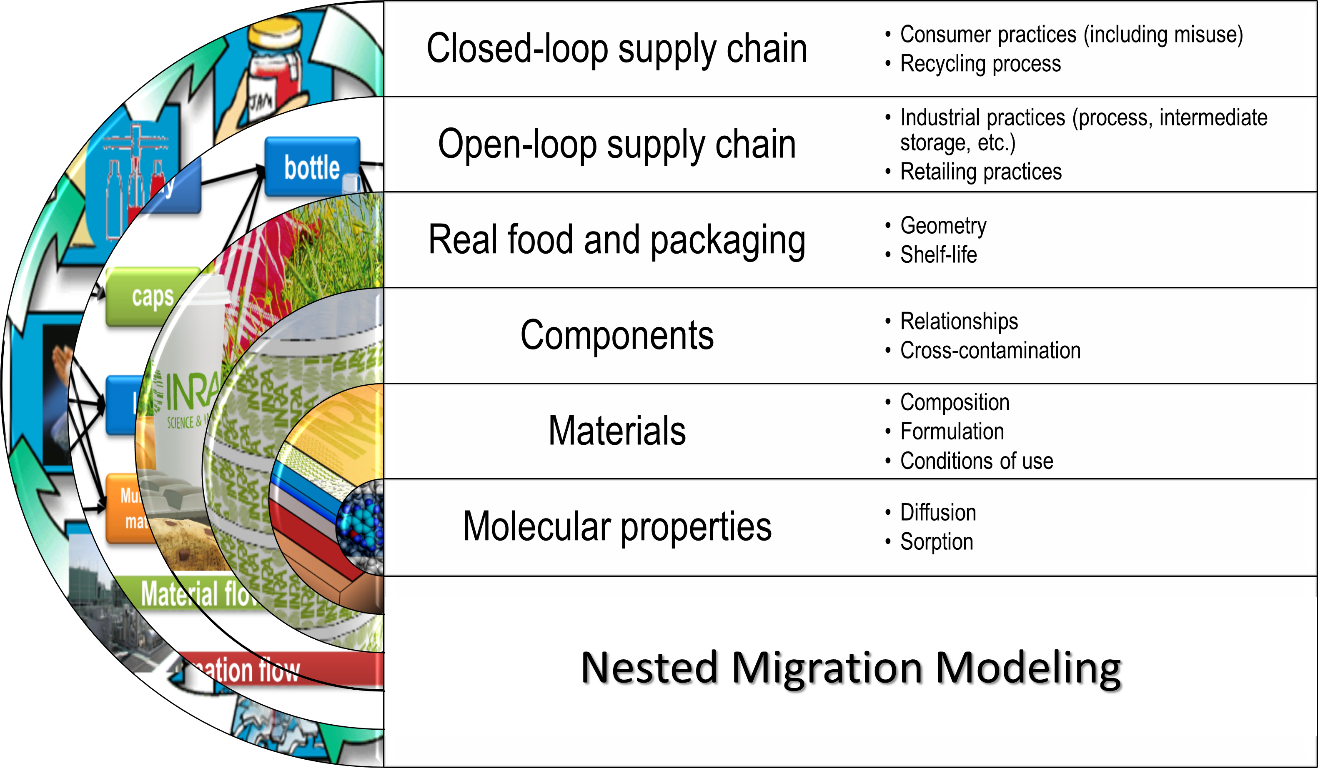

There is no limit to the scope of modeling in current regulations and practices. Compliance testing can be seen as the simplest usage of modeling and validating a closed loop of recycling as the most complex application (see Figure 1). Repeated use, composite materials and safe-by-design approaches can be envisioned of intermediate complexity. All applications (small and large) obey in fact to same global scheme, where the result obtained at the scale immediately below is used at the upper scale, as shown in Figure 4, The complexity of modeling relies on the number of scales considered and not on the system (film, bottle, etc.) subjected to the modeling activity. The keys to identifying the number of scales, components and steps are discussed all along the chapter.

Figure 4. Overview of the nested modeling strategy to predict migration for all applications depicted in Figure 1.

4.1.2 Modeling using a tiered approach: from worst-case scenarios to detailed conservative ones

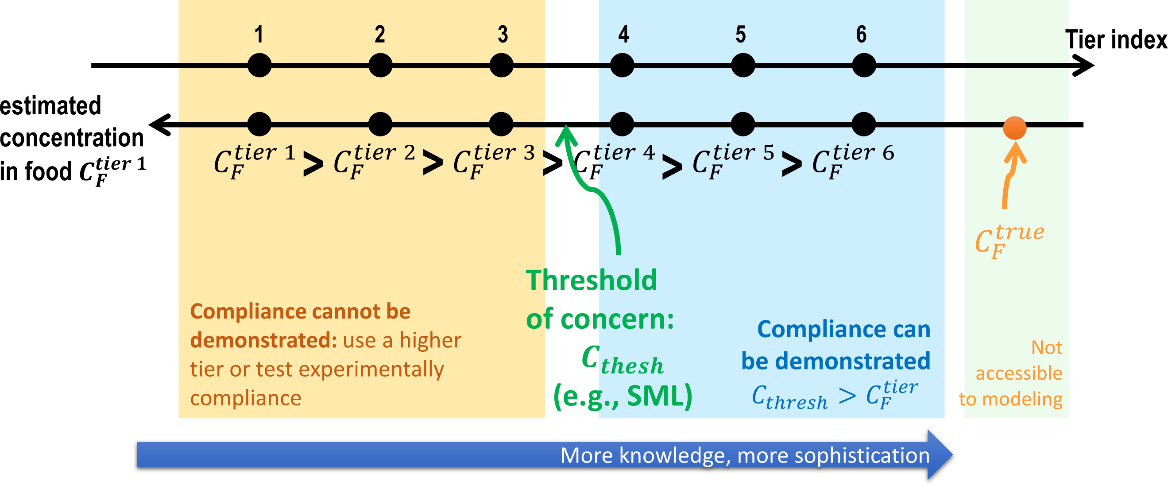

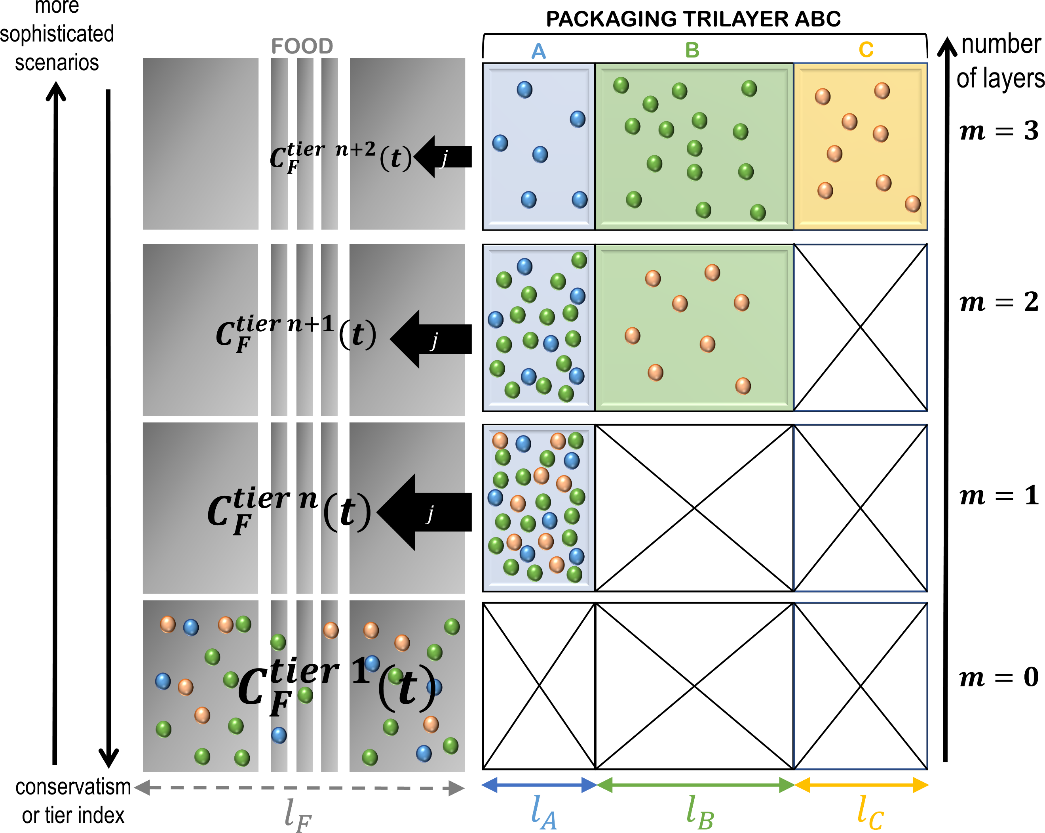

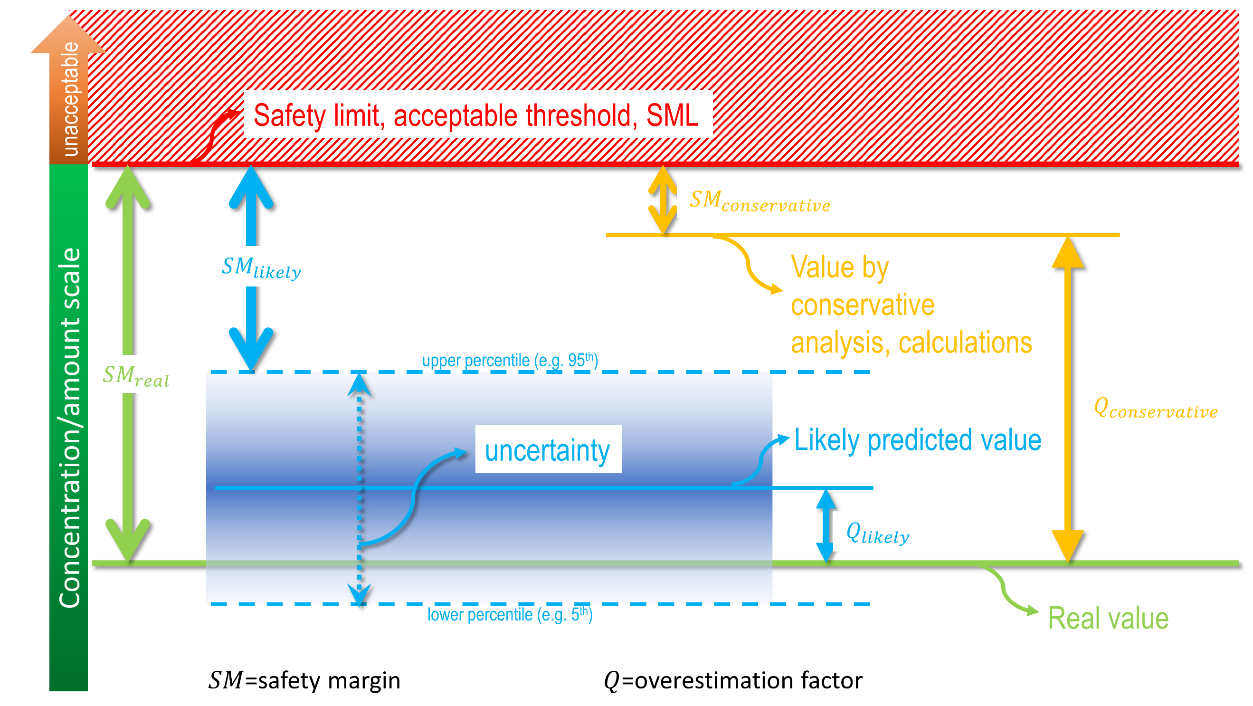

The exact value of the contamination of the food is never achievable because the conditions of contact are variable (time, temperature) between comparable products and because our knowledge of molecular mechanisms is perfectible. As a result, the practice seeks successive approximations of the migration in a tiered approach, as shown in Figure 5. At the first tier, the estimation is very coarse and connected with the highest overestimation factor. If the determined concentration at tier is higher than the threshold of concern, the next tier is triggered by introducing substantial refinements and details, and so on. The process stops when no additional information can be introduced (experiments need to be preferred) or when the calculated concentration is lower than the threshold of concern. The lowest tier within the threshold of concern defines the proper level of knowledge required to demonstrate compliance or to guarantee the safe use of a material, substance, or process. There is no systematic procedure to identify the minimum tier to reach the goal, and only the needed information can be listed.

Figure 5. Principle of the tiered approach to demonstrate compliance for food contact materials. Compliance is demonstrated as soon as the estimated concentration is greater than the threshold of concern. Tier 1 is usually associated with total migration (see Eq. ).

The possibilities and prerequisites for using modeling in compliance testing are reviewed in Table 3. The mentioned tiers , and * are indicative and corresponded to a modeling level more sophisticated than the first tier. The first tier is usually coined to “total migration” and corresponds to the total transfer of substances into food (see Figure 13). The corresponding concentration in food, , is determined by a “dilution” model:

where is the initial concentration in the material (regardless its distribution) expressed in mass per volume (preferred in this work) or in mass per mass (industrial practice). is the material-to-food volume or mass ratio. When one-dimensional representations are used, is also the ratio between the thickness of packaging walls, denoted , and the characteristic dimension of the food, denoted , where is the effective surface area in contact, counting usually the total surface area in contact with the food and the headspace. By contrast, the food volume is restricted to the condensed part of the food (solid or liquid).

Table 3. Prerequisites to use calculations as an alternative to migration testing.

| Prerequisites | Type of estimate | Examples of works | tier† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Migration modeling or related calculations | lectures , reference text books (specific or general) | Lectures on migration 82-84, text books on migration 85-90 ; reviews and case studies on migration modeling 86, 89, 91-95 96-98 ; reference text books on packaging90, 99; reference text books on mass transfer100-107 | R1 R2 R2 R3 R3 R3 |

| Identity of material | technical specifications, recycling code, measurements | supplier, regulation, standard 108, 109, FTIR spectra | R1 R2 R3 |

| Characteristics of the polymer | density , glass transition temperature , crystallinity | supplier; handbooks110, 111; measurements | R1 R2 R3 |

| Identity of the substance | real substance , chemical structure, chemical descriptors | supplier; deformulation 112 and/or spectroscopy 113, 114; analoguous substance | R1 R2 R3 |

| Packaging geometry | 1 kg packed in 6 dm2 , 1D approximation of real geometry, 3D real geometry | regulation; supplier, end-user; research work111, 115-118 | R2 R2 R3 |

| Contact conditions (time, temperature, phase in contact…) | standard test conditions , accelerated conditions, real conditions | end-user; regulation | R1 R2 |

| Initial concentration | real values, overestimates | supplier; guidance, orientation formulabrute force deformulation 113, 114 | R1 R2 R3 |

| Diffusion coefficients (see §**5)** | real values, overestimates, molecular theory, molecular modeling | measurements, literature 119-130 Piringer model131 or equivalent 100; free-volume theories and their extensions123, 124, 126, 132-136 ; Molecular Dynamics simulation 137-142 | R1 R2 R3 R3 R3 R3 |

| Partition coefficients or sorption isotherms (see §**6)** | real values, overestimates, molecular theory, molecular modeling (Flory Approximation), molecular modeling | measurements, literature; guidance 143; Kirkwood-Buff theory 144 ; Flory -Huggins theory145-148; solubility parameters 110, 112, 149, 150 ; theory of interacting liquids151; thermodynamic integration, insertion method 152-157 at atomistic scale; atomistic calculations within the Flory approximation112, 113, 158-164 | R1 R2 R3 R3 R3 R3 R3 R3 |

| Mass transfer resistance in the contacting phase (see §**4.2.3.4)** | none, correlation diffusion coefficient, flow | worst-case; liquid or gas model 100, 101, 103-105, 165-167; Graetz type problem; full simulation coupling168 | R1 R2 R2 R3 |

| Acceptable thresholds (see §**8.4.1)** | 37-39, 37, 38, 169-174, threshold of regulation175 , 176 | Regulations; regulation policy 74 ; recommendations (GMP), literature | R1 R2 R3 |

†Recommended for compliance testing at the first (), second () and third () tier. If the value of the migration is larger at the second tier than at the first one, use the second tier. If the value of the migration is larger at the third tier than at the second one, use the third one. =*specific migration limit; =maximum amounts; = threshold of toxicological concern; =good manufacturing practices. and maximum concentration in food are related as , with and the food and packaging volume respectively, the density of the polymer and the partition coefficient.

4.1.3 Key steps in migration modeling and risk assessment approaches

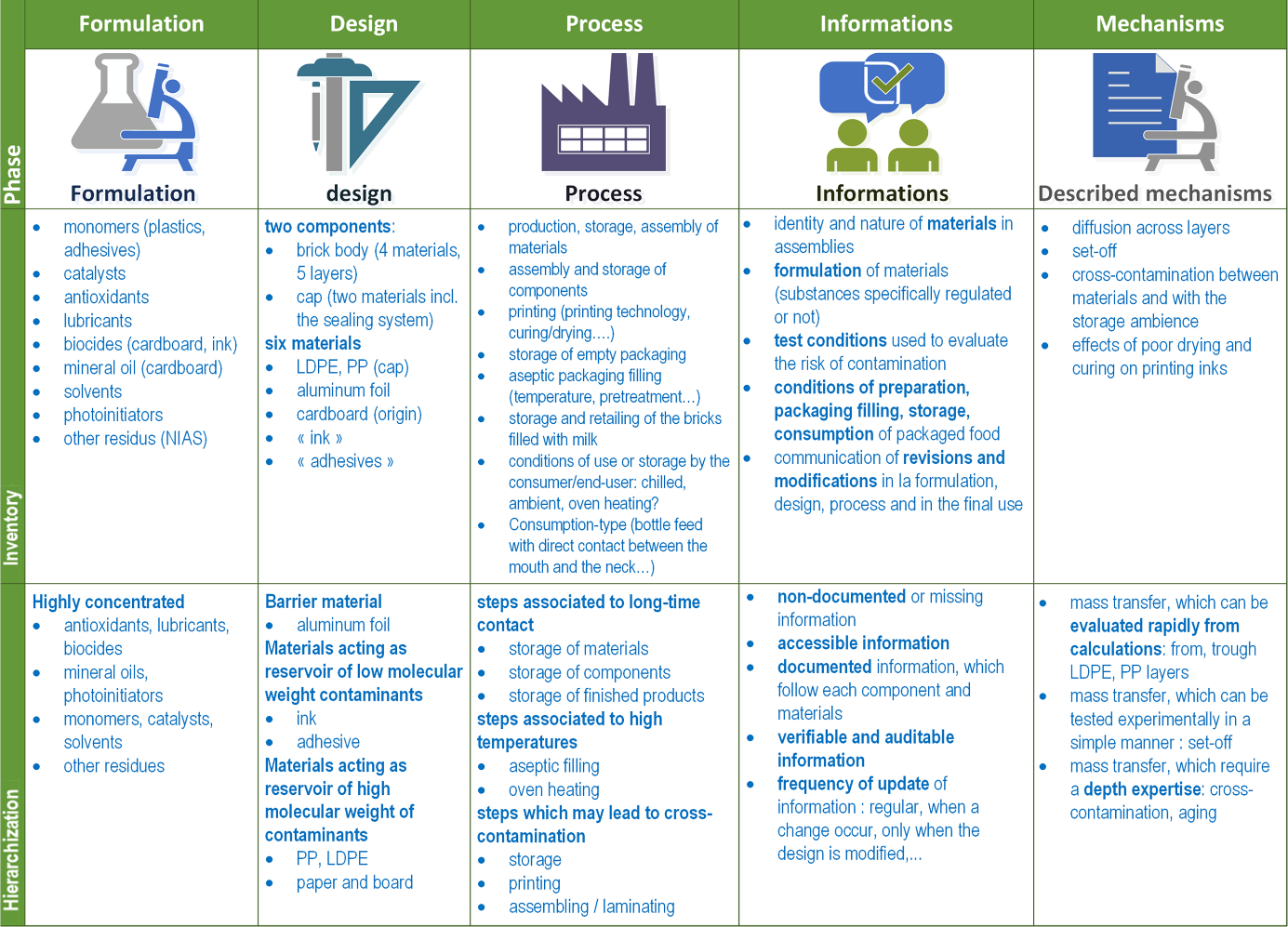

Any migration modeling for compliance testing, risk assessment, and safe-by-design approaches should be initiated by the review of five important sections with an intent of providing an inventory on:

- the formulation of materials (intentionally-added or not substances),

- the components included in the design;

- the steps followed by the material, the finished packaging, and the packaged food;

- the information obtained from suppliers, regulations, industrial recommendations;

- the described mechanisms of contamination.

For each section, the items need to be ranked and prioritized according to their suspected or foreseen importance on the contamination of the packaged food, as shown in Figure 6. The principles and illustrations described in this chapter can be used to extend the systems, steps, substances,… under scrutiny beyond primary food packaging and contact layers.

Figure 6. Generic steps to review in migration modeling and safe-by design approaches. The depicted example corresponds to the review for a new aseptic carton packaging for milk to be consumed by infants.

4.2 Migration modeling for compliance testing and beyond

In agreement with EU recommendations 80, this section details the assumptions and conditions suitable for compliance testing at high tiers using a comprehensive description of mass transfer. The levels of description would correspond to tiers and in Table 3.

4.2.1 Principles of migration modeling

Highlights on the principles of migration modeling.

- Migration obey simply speaking to the well-known laws of diffusion.

- The mass transfer from one material to another material, or the food requires specific treatment and attention as it is not implemented by default generic numerical software (commercial or not).

- One-dimensional mass transfer calculations are sufficient for most of the applications if mass balances are well preserved.

- The cost of modeling is dramatically reduced by simulating the contacting phase implicitly with proper boundary conditions. It is important to note that the substances within any eventual mass transfer boundary layer are not included in the food mass balance when implicit models are used.

- Beyond its obvious numerical advantages (abacuses, master curves, pre-tabulated results), dimensionless formulations based on similitude principles facilitate the review of model assumptions and results.

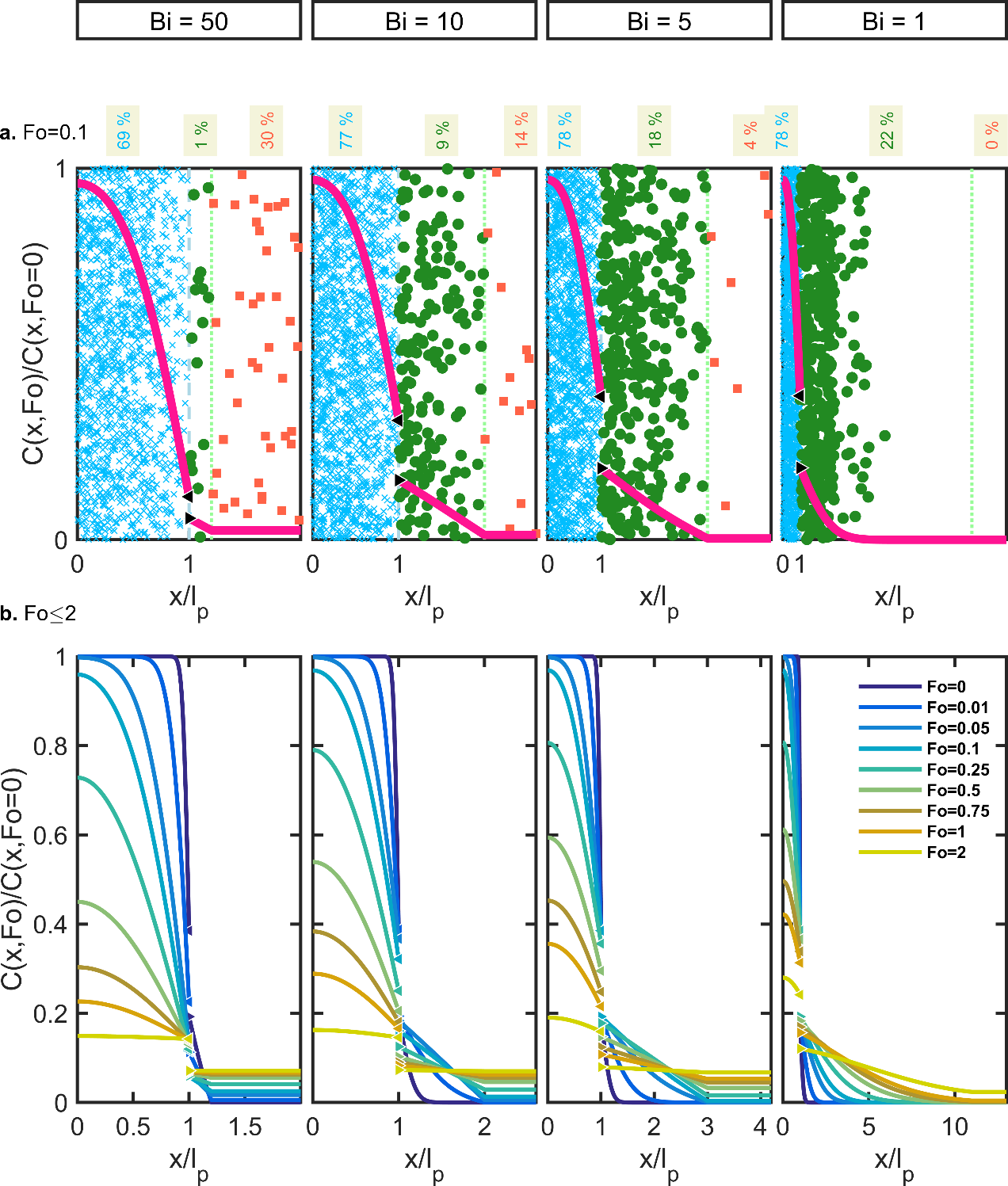

Substances non-covalently bound to the polymer are subjected to thermal agitation, which causes in return a random translation of their center-of-mass. Each additive, monomer, residue jumps or walks randomly in the polymer matrix from one accessible void to the next one. The substances reach the interface eventually with the food, where the same hopping process is repeated usually at a higher pace. When volatile substances meet a gas phase, their skew trajectories are governed by the collision with gas molecules. In all cases, random walks occur in three-dimensions, but a concentration gradient develops only at leaching interfaces, in its perpendicular direction. As the walls of the packaging are thin compared to the characteristic food dimension, migration can be approximated as a one-dimensional mass transfer problem as shown in Figure 7. The migrating substances are depicted either as individual molecules or solutes (i.e., scales are not respected) showing microscopic concentration fluctuations or as smooth macroscopic concentration profiles (continuous lines). Different symbols are used whether the solutes are in the polymer (position ); in a small boundary layer in the food and of thickness , where a concentration gradient exists (position ); or in the food bulk () without any significant concentration gradient (e.g., assumption of a perfectly mixed medium). Choosing as a free parameter enables to cover almost all contacting phases (gas, liquid food or simulant, solid and semi-solid food) with reasonable complexity.

Figure 7 plots simulation results using the concepts of statistical physics (i.e., the molecules jump randomly vertically and horizontally without “knowing” where the interface is located) and by using the concept of continuum mechanics (i.e., balance on populations and macroscopic fluxes on elementary volumes). The stochastic and deterministic point of views are equivalent and highlight that the observed macroscopic gradients are the consequence of the evolution of the distributions of solutes with time and not its cause. In the upward direction, the random displacements are compensated by the same and opposite microscopic flux in the downward direction. The net balance is zero, and no concentration gradient can develop. The substances translate at the same frequency in the horizontal direction (i.e., isotropic diffusion), but since no solute comes to compensate the flux from left to right at the beginning of the contact, a net flux develops from left to right, resulting in the spreading of a concentration gradient from the source (the polymer: ) to the food (the food: ). Statistical physics and continuum mechanics counts molecules in a very similar fashion, via the concepts of probability density, and of volume concentration , respectively. is the total number of migrating substances in the whole system and the number of molecules in an elemental volume . The concentration at the interface between F and P (denoted P-F) requires specific treatment and analysis. Since the principle zero of thermodynamics does not hold for mass transfer, both density and concentration are discontinuous at the P-F interface. If no reaction occurs at the interface, the mass balance is kept across the interface (i.e., no substance is lost). Additionally, the principle of microscopic reversibility entails that the amount of substances crossing the interface per time unit from left to right (denoted P→F) is exactly matched by the amount of substances crossing the interface in the opposite direction (denoted F→P). In other words, any substance located exactly at the interface has the same probability to go in P and F, irrespectively its origin. This principle of microscopic mass balance reads:

where is the frequency of translating from the compartment A to the compartment . The concept of local chemical equilibrium developed among others by Henry Eyring provides a robust framework to express the frequencies of passage from one state to another one without justifying the details on how the change in conformations and local velocities affect the passage from A to B. The frequency of passage is written as:

with the free energy associated to the transition state and the free energy of sorption of the solute in A. The preexponential factor is independent of temperature; its expression depends on the statistical ensemble used to express probabilities. By combining Eqs and , the molecules distribute across the interface with a ratio of probabilities equal to:

where and indicate the position and time; the food-packaging interface is located at . The concentration profiles are, hence, continuous across the P-F interface only when the free sorption energies are similar in both compartments. In the general case, the concentration profile is discontinuous across the interface. Figure 7 plots cases for an apparent partition coefficient of 0.5. In other words, the substance has a twice more chemical affinity for P than for F, as expected for plastic additives and monomers. For conservative migration modeling, values of higher than unity are preferred to maximize the gradient and consequently the amount transferred to the food. When the release of substance does not modify the properties of the polymer (polymer densification, a shift of the glass transition temperature ), the ratio of concentrations is likely to be constant at the interface.

Figure 7. One-dimensional description of solute diffusion (e.g., additive, monomer) from the packaging wall (position: , individual solutes identified as ×) to the contacting phase (individual solutes identified as ■) via the food boundary layer (individual solutes identified as ●): (a) random distribution of solutes and corresponding concentration profile at and (b) after contact times up to . The percentages in the top part represent the residual amount in each compartment.

4.2.1.2 Migration modeling and similitude properties

Under the assumption of uniform and constant transport and thermodynamic properties in each compartment (polymer: P, boundary layer: BL, bulk contacting phase or food: F), the mass transfer problem is self-similar according to a small number of dimensionless parameters or ratios. According to the principle of similitude, a real problem can be compared to a theoretical case without dimensions if all independent dimensionless quantities are similar. The key dimensionless quantities are reviewed in Table 4.

Table 4. Key dimensionless quantities of the migration from monomaterials. Contact is assumed to be initiated at .

| Dimensionless quantity | Meaning | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensionless concentration | is a reference concentration, usually the initial concentration in the polymer . | |

| it is defined from Eq.. (4) | Partition coefficient | At macroscopic equilibrium, it is also defined as with and the volume-averaged concentrations in F and P, respectively. |

| Dimensionless position | is characteristic food dimension, usually the thickness or the ratio if the geometry is complex, with the volume of the material and the surface area in contact with . It is recommended to maximize by also including the headspace in the calculations of . | |

| Dimensionless time | is the diffusion coefficient in the polymer at the temperature of contact. The integral form needs to be preferred if the diffusion coefficient is variable with time (temperature change) | |

| or | mass Biot or Sherwood number | where is the thickness of the boundary layer and the diffusion coefficient in F, such that is the effective mass transfer coefficient across the boundary. |

| Dilution ratio | This number is defined as the ratio of characteristic lengths and controls how the substances are diluted in the food, usually much larger than the packaging. |

4.2.1.3 Explicit vs implicit food representation

It would be logical that migration models describe, how the migrants distribute in the food explicitly. Solid foods, such as a chicken or a pizza, are not expected to have all parts contaminated similarly. For risk assessment, we consider that all parts are intended to be ingested, including the most contaminated sauce in contact with the packaging. As a result, only a global estimate of the food contamination is required, as measured with a liquid simulating the entire food. Replacing a solid by a liquid or vice-versa has a consequence on the rates of mass transfer. This part discusses the differences between explicit and implicit representations of the food and of the risk to underestimate the real migration.

Figure 7 represents explicitly mass transfer in the food, that is the concentration profiles in the food are also calculated. The depicted cases correspond to a characteristic food length of (i.e., thin food to make the boundary layer visible). The total domain has a length of . When the food is represented explicitly, the amount transferred to the food is defined as:

Eq.(6) accumulates substances in the boundary layer (round symbols) and in the food bulk (square symbols). Implicit food representation will describe mass transfer only in the packaging and apply a proper boundary condition between the food and the packaging at the position . With the help of Eq. , the flux at the interface, denoted , can be expressed only with concentrations taken inside the packaging or in the food far from the interface, .This assumption open the way of an implicit representation of the food via a boundary condition relating the diffusion at the packaging-food interface with the flux entering into the food:

Eq. (6) offers a good approximation of the explicit representation when the contact time is sufficient to reach a fully developed concentration profile (linear, so-called Prandtl approximation) inside the boundary layer. The critical Fourier number is given by . The profile plotted in fFigure 7a for and deviates from the assumption above. The critical Fourier number is, indeed, of 1.67 and the value of is close to zero, whereas the food is already contaminated via its boundary layer. Implicit food representation approximates the concentration in the food, , by its concentration far from the interface. By noticing that the flux is taken after the boundary layer, one gets:

For and if the threshold of concern is not too low, the amount present in the boundary layer can be neglected (less than 1% in Figure 7a when ) and an implicit representation can be used. Its main advantage is the dramatic reduction of the problem complexity and of the computational time. In very thin or low barrier films and in solid foods, the implicit food representation may underestimate the contamination of the food severely. The amounts in the boundary layer reported in Figure 7a reach 9%, 18% and 22% for = 10, 5, 1 respectively. When an implicit representation is used, calculating the concentration in the food from the mass balance in the packaging between and does not solve the issue as the closure equalities are enforced at any time:

The amount present in the boundary layer is always neglected in migration representing the food implicitly. Only by choosing artificially as a worst-case scenario makes this amount negligible at the price of migration much faster than the one expected in the real conditions.

4.2.1.4 Other assumptions

We describe in this section the constitutive equations to describe mass transfer from monolayer and multilayer materials, when the food is represented implicitly via the boundary condition and the food mass balance (8). The total packaging thickness is denoted for a packaging (e.g. laminate) consisting of layers. At the position (usually the surface exposed to the ambiance), an impervious boundary layer is assumed so that the amount transferred to the food is maximized. All substances are assumed to be well dispersed where they have been incorporated (e.g., no blooming effect) and below their concentration at saturation (i.e., no supersaturation).

4.2.2 Governing equations for monolayer materials

4.2.2.1 Overview

The full set of equations for monolayer materials including the initial condition (IC), the transport equation (TE), the boundary conditions (BC) and the mass balance on the food compartment (MB) reads:

where is an exponent controlling the system of coordinates ( : Cartesian, : cylindrical; : spherical); is the diffusion coefficient possibly variable with concentration (e.g., case of plasticizers used at high concentrations).

When the diffusion coefficient in the packaging is considered constant along with , Table 4 and system 9-13 yield the following dimensionless formulation for Cartesian coordinates:

When , the third type boundary condition at (Robin boundary condition) can be replaced by a simple coupling with the mass balance. By differentiating BM respectively to , one gets:

The worst-case scenario, and corresponds to the Dirichlet boundary condition .

4.2.2.2 Concentration in the contact phase at thermodynamical equilibrium

According to Eqs. , the maximum concentration in food is obtained at thermodynamical equilibrium ( ):

In practice it is convenient to express the kinetics of desorption in food as a function of the fraction of the equilibrium value:

4.2.2.3 Dimensionless migration kinetics and their analytical approximations

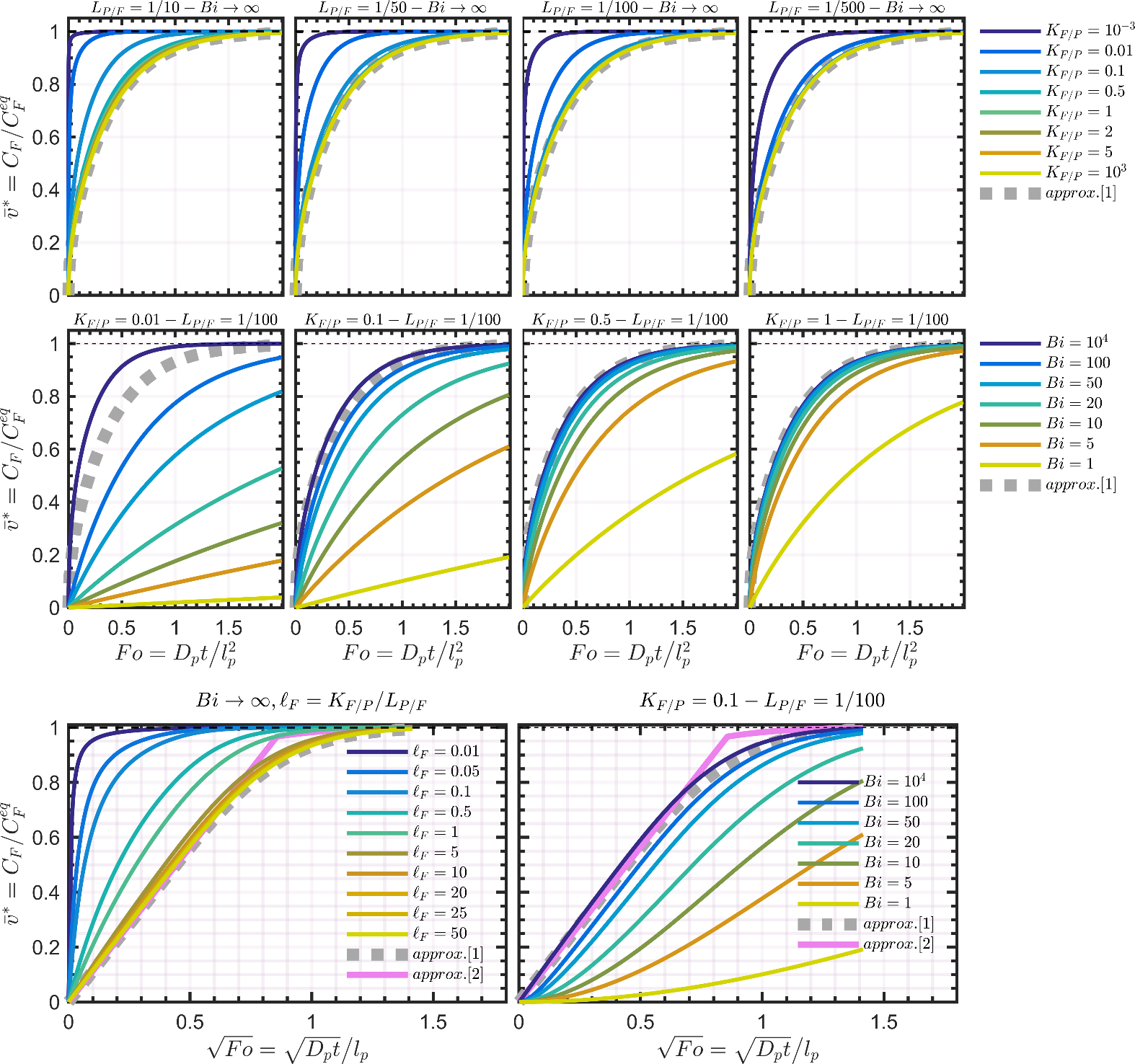

The dimensionless migration kinetics are plotted in Figure 8. The analytical solution associated with the Dirichlet condition is given by Eq. 4.18 in Crank’s book 102 and reads :

For small values, the approximation requires to be very large (103 or 104) and a more efficient approximation can be obtained by combining an approximation of Eq 4.20 in Crank’s book 102 with Eq. for as:

Approximations and are plotted along with the results of numerical simulations in Figure 8. The common assumption of the linearity of with is well verified while and when the equivalent length of the contacting phase and are large. At intermediate values, the Dirichlet condition offers a conservative approximation (i.e., is overestimated) and Eq. can be used safely for compliance testing. However, when (e.g., small food volume, low chemical affinity for the food), Eq. must be avoided due to a significant risk of underestimation of low values. The equilibrium is, indeed, reached much faster due to a much smaller amount to transfer and because the concentration at the F-P interface never vanishes. An accurate estimation of migration requires ad-hoc numerical solutions or special analytical solutions. In mathematical terms, finite volume effects cause the propagation of shockwaves between the polymer and the contacting phase: the addition of substances to F modifies instantaneously the capacity of P to transfer additional substances, and so on for the next substances creating positive and destructive interference across the mass transfer boundary layer when it exists. One practical consequence is that analytical solutions are without closed-forms and therefore more complex than Eq. XXX.

- For and , the analytical solution verifying finite volume effects and boundary condition is given by Eq. 4. 37 in Crank’s book 102 and is very accurate at a reasonable cost for .

- For arbitrary and values, new solutions verifying the general boundary condition (see Refs. 127, 177-179). Short-time and long-time solutions were optimized for efficiency and to integrate more complex physics such as non-linear sorption isotherms or for boundary conditions variable in time.

The general solutions are not detailed here as their expressions exceed the scope of the article. When , the Eq. 4. 37 in Crank’s book 102 reads:

The zeros of the transcendental equation, , increase with and also when decreases. This behavior demonstrates that converges exponentially and more rapidly to equilibrium whenvalues are low. The linearization with ceases to be correct earlier and is associated to slopes varying with . As the values of are usually not tabulated beyond in reference text books (see Table 4.1, p. 379 in 102, it is recommended to restrict the use of Eq. XXXX to .

Figure 8. Dimensionless desorption kinetics for various values of , and with . Approximations [1] and [2] are given by Eqs. XXX and XXX , respectively.

4.2.3 Governing equations for multilayers

Highlights for multilayers

- Multilayer can be seen as a generalization of monolayer materials but with additional features such as functional barriers (delayed migration) and reservoir layers (accumulation inside one or several internal virgin layers).

- When the partition coefficients between layers and their diffusion coefficients are constant with time, the total migration is the sum of the migrations associated with the contribution of individual layers.

- Uncertainty in partitioning and the initial distribution of migrants can be overcome by moving “artificially” the content on one layer to a layer closer to the contacting phase.

- The calculation procedures presented in this section have been introduced in the guidance to EU Regulation 10/2011/EC.

4.2.3.1 Thermodynamical assumptions The case of materials consisting of materials or layers ( ) can be seen as a generalization of the monolayer case ( ) at the expense of a few additional assumptions and conventions. Because monolayer systems were dominating in the 20th century, the reasoning supporting US and EU regulations was, hence, devised based on an assumption of a migration without delay and obeying to a scaling proportional to the square root of time. The conventional condition of ten days at 40°C was thus thought to be equivalent to a test of one hundred days with a factor comprised between unity (equilibrium) and (. Moving the substances away from the P-F interface delays substantially the mass transfer to the contacting phase. This behavior is central to the concept of functional barrier 180; it was initially explored to promote the incorporation of recycled material – possibly contaminated due to post-consumer misuse or mixing with non-food grade materials – in co-extrudates. The recycled polymer is sandwiched within two layers of virgin polymers. Similar problems can be resolved only by adapting the initial condition in the equation system (9) to the need instead of using a uniform distribution. When the materials are different in nature, a contact condition similar to Eq. (4) needs to be considered. The proposed description relies on an assumption of a linear and reversible sorption of substances in each layer so that a linear sorption isotherm is assumed in any layer, including in the food. By denoting the partial pressure of the migrating substance, the isotherm associated to the Henri constant reads for each layer:

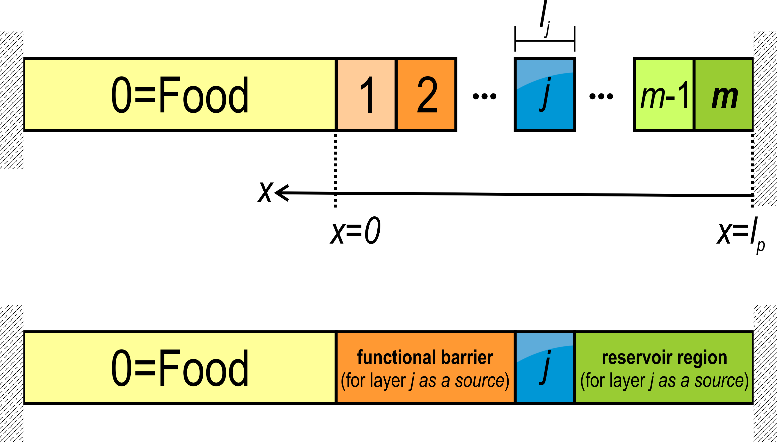

(17) With a sake of generalization, the layers including the food are indexed from (food: F) to (layer the most distant to F), with being the contact layer, as shown in Figure 9. The residual concentration in each layer is for and .

Figure 9. Indexing rule of a material including m layers (total thickness ) in contact with a food product indexed 0. The left and right external boundaries are considered impervious (no mass loss). The concepts of “functional barrier” are “reservoir” assume that the layer j is the source (with non-zero initial concentration). It is used in §4.2.3.5 and §4.2.3.6.

4.2.3.2 Concentration in the contact phase at thermodynamical equilibrium

The Henri isotherm defined in Eq. (17) offers a robust but simplified thermodynamic representation of the variation of the chemical potential with the local composition in the system. The validity of the model and its generalization are discussed in §6.2 . Partial pressure [p\left( x,t \right)] is a continuous potential, and thermodynamical equilibrium is achieved when its value is uniform across the structure. By neglecting mass losses, Eq. (17) and the mass balance between and enables to generalizes Eq. (12):

(18) where is the partition coefficient between the layer and the food.

4.2.3.3 Transport equations

Transport equations are unchanged and are piecewise-defined:

(19) and connected at internal interfaces via the double conditions of mass conservation and local thermodynamical equilibrium:

(20)

4.2.3.4 Limiting mass transfer resistance

A dimensionless formulation of Eqs (6), (19) and (20) is achievable at the expense of choosing a reference layer, , setting the reference time scale . In numerical algorithms, where stability and convergence are very stringent, it is convenient to choose as a reference layer, the layer associated to the highest mass transfer resistance (lowest permeability) is the best choice:

(21) If several conditions need to be compared, a natural choice is to choose the contact layer as the reference layer ().

4.2.3.5 Typologies of migration behaviors

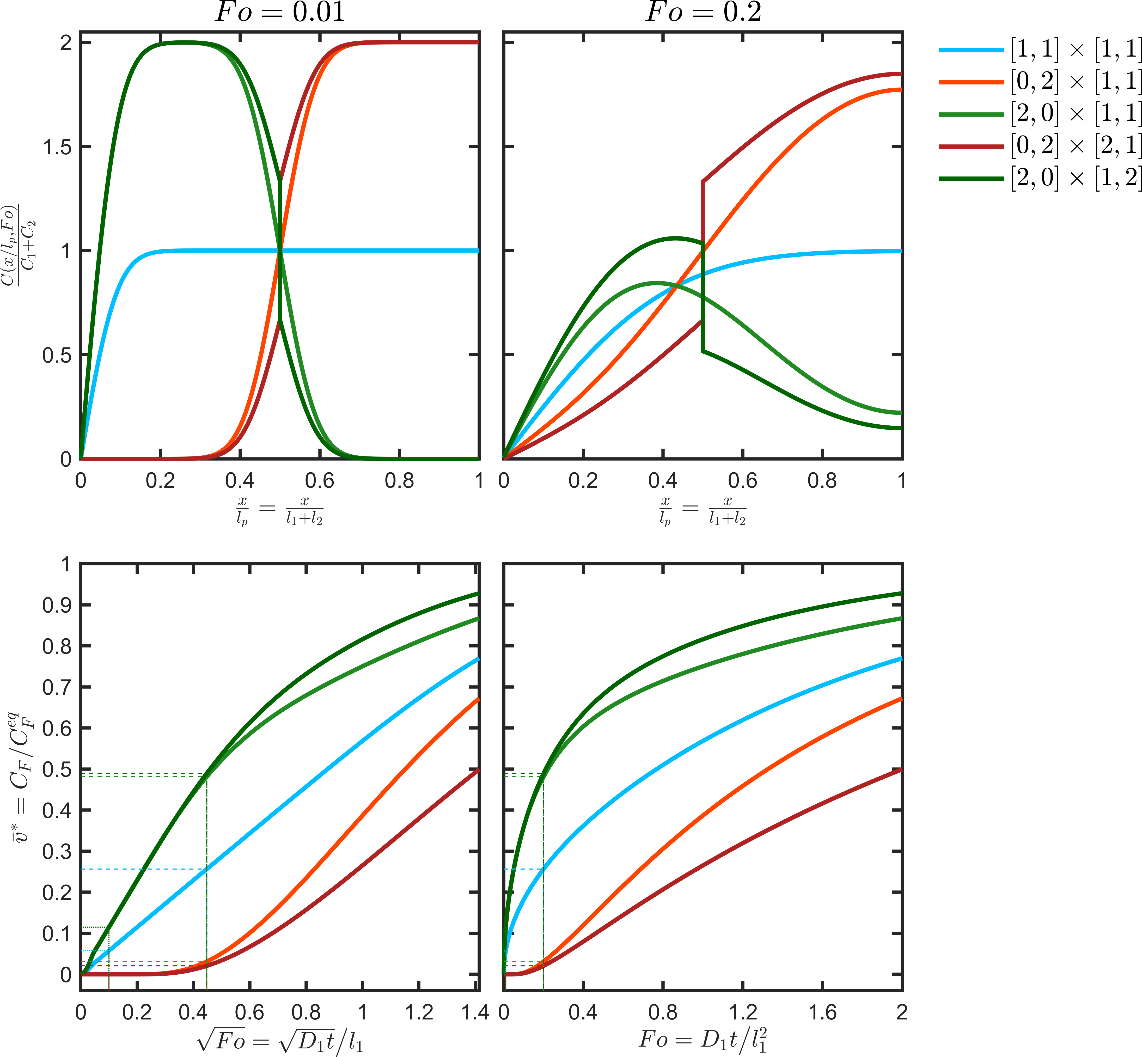

The main behaviors, which can be observed with multilayers, are illustrated in simple configurations corresponding to a bilayer structure (each layer has a thickness ) in contact with a liquid phase with a characteristic thickness and associated to . The five considered cases are summarized in Table 5 and were associated with a similar initial amount and comparable final concentration in the contacting phase ca. . The other parameters were , , and the time scale . The calculated profiles and kinetics corresponding to the five scenarios are plotted in Figure 10.

Table 5. Illustration of the main behaviors associated with multilayer structures. The concepts of functional barrier and reservoir are illustrated in Figure 9.

| interpretation | code | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | uniform distribution (equivalent to a monolayer) | [1,1]×[1,1] |

| 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | functional barrier (barrier to diffusion only) | [0,2]×[1,1] |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | reservoir layer (same capacity) | [2,0]×[1,1] |

| 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | functional barrier (barrier to diffusion and of solubility) | [0,2]×[2,1] |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | reservoir layer (twice less capacity) | [2,0]×[1,2] |

Monolayers and functional barriers lead to uniformly decreasing concentration profiles. The corresponding desorption kinetics in F are respectively proportional to the square-root of time and proportional to time after some lag time equal to . For the same initial amount in the structure and after the lag time, the functional barrier ceases to operate and leads to a migration proportional to . Only a functional barrier combining a diffusion barrier ( ) and solubility one ( ) can slow down the desorption durably. Reservoirs behave very differently; they are associated with non-monotonous concentration profiles, accelerated desorption kinetics while converging to a very similar concentration at equilibrium. For the same initial content and when the barrier on the right is higher than the barrier on the left , the “reservoir” configuration overestimates the migration kinetics associated with all other configurations.

Figure 10. Concentration profiles (top) and migration kinetics (bottom) for the bilayer structure and scenarios detailed in Table 5.

4.2.3.6 Superposition principles and conservative scenarios for multilayer and multicomponent systems

Mathematical principles

Multilayer structures offer a broad range of behaviors. In the simplest cases, as shown in Figure 10, desorption kinetics are monotonous with time. It may be not the case if the functional barrier and reservoir effects are combined. The calculations for complex multilayer are complicated by the difficulty to associate the uncertainty in diffusion and sorption properties on the concentration in food. For monolayer materials, a conservative scenario is achieved by overestimating simultaneously , and . For multilayer materials, no similar rule holds. Intuitively based on the illustrated configurations in Figure 10, it can be stated that for the capacity of the layer to transfer its content, (amount transferred to F at the time ), is maximized (denoted ) if the following properties are fulfilled:

Conditions have a mathematical justification in the linear properties of the equations -. The solution of any linear decomposition of the initial concentration profile is equal to the sum of the individual solutions:

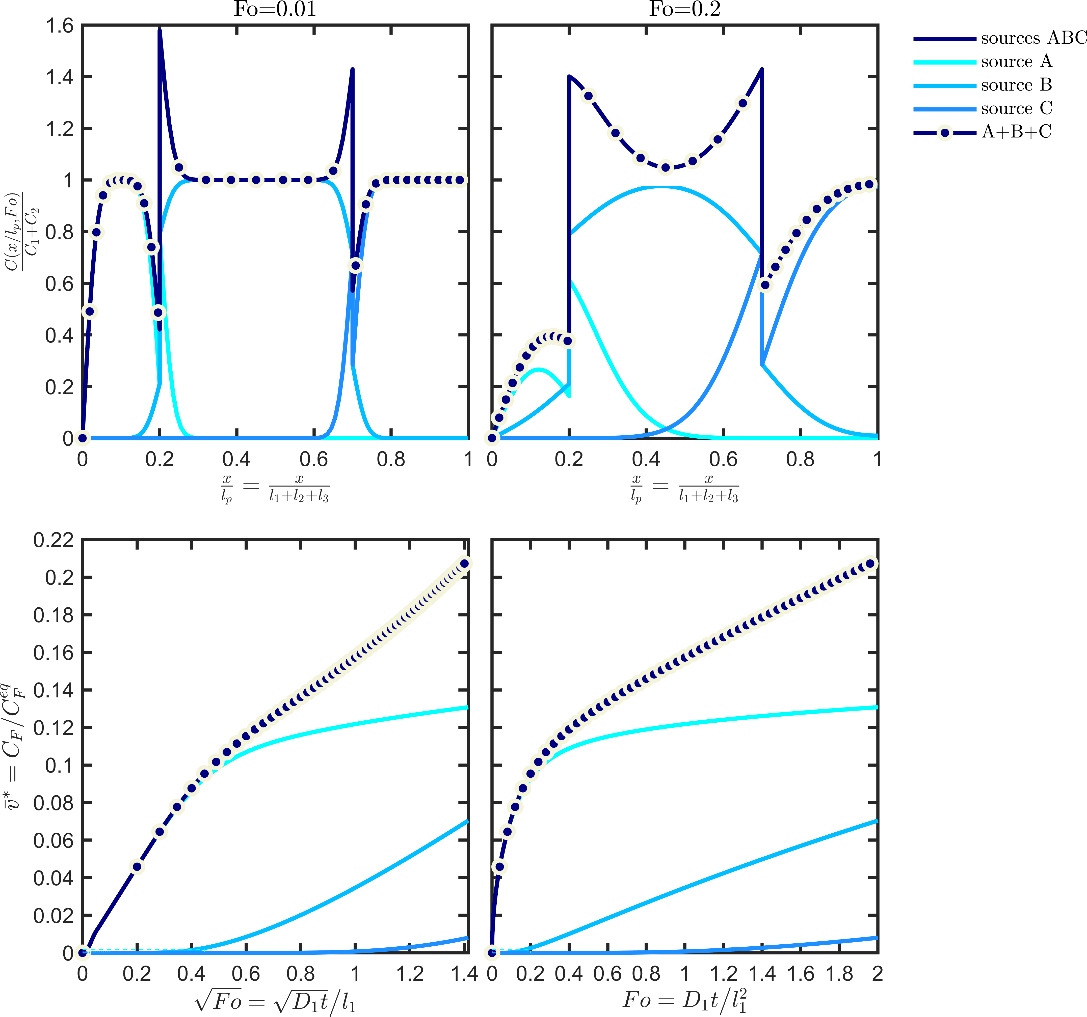

Example for a trilayer material ABC

Eq. XXX is particularly significant as it is valid for any partitioning of the source terms in the material, respecting or not the positions of the layers. An application of the additivity ofvalues (concentration profiles and kinetics) is shown in Figure 11 for a trilayer structure ABC detailed in Table 6.

Table 6. Parameters used to construct realistic and conservative migration scenarios depicted in Figure 11 and Figure 12. Quantities are expressed respectively to the likely values† for the first layer (the three layers ABC are indexed 1,2,3). They are scalar when the contribution of each layer as a source is considered in combination with others (the three sources are considered at once). The contributions of individual sources are indicated by 3×1 vectors mentioning the properties of all layers considered as a source or not.

| property | case-study (likely) contribution of the jth layer | conservative scenario (high tier) contribution of the jth layer | worst-case scenario (low tier) contribution of the jth layer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | none | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | [1,0,0] | [0,1,0] | [0,0,1] | 3.5 | 0.6 | none | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | [1,10-3,10-3] | [1,1,10-3] | [1,10,10] | 1 | 1 | none | |

| 0.3 | 0.8 | 2.0 | [10,10,10] | [1,10,10] | [1,1,10] | 10 | 10 | none |

†Likely value = true value or close to the true value in the considered scenario.

The simulation of each layer individually underlines the different mechanisms controlling the contribution of each layer: reservoir effect for source A (scaling of desorption kinetics with the square root of time) and functional barriers for B and C (desorption kinetics linear with time after significant lag-times). The depicted profiles are assumed to the “likely” or “true” ones. They are considered inaccessible to simulation and should be approximated at some tier in a way that the concentration in F is always overestimated (see Figure 13).

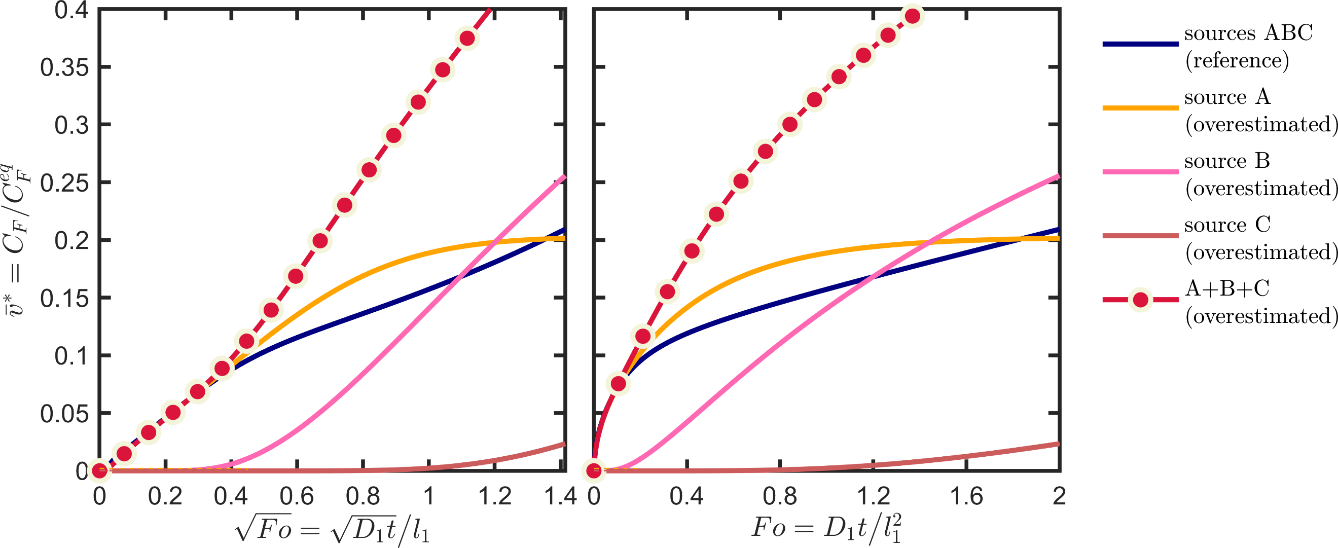

Figure 11. Illustration of the additivity of the sources (see Eq. ) for a trilayer structure ABC associated with the case study detailed in Table 6: concentration profiles (top), kinetics (bottom). The case “sources ABC” is obtained by simulating the whole structure. The result A+B+C corresponds to the mathematical addition of the contributions of the three sources.

Eq. XXX provides a numerical procedure to devise conservative scenarios for multilayer structures. A similar procedure has been detailed in the section 4.2 of the European guidance document 143. We repeat here the procedure for the sole overestimation of the chemical affinity effects and by keeping the diffusion coefficients to their “likely” values. The core idea is to prevent or hinder the diffusion of the substances in the jth layer to the right (by assuming that the food is on the left) and to facilitate their desorption to the left, to bring the contaminants closer to the food. The “conservative scenario” of Table 6 applies a factor ten to the Henry-like coefficient(s) of the source and behind. The likely and values are kept for the layers between the food and the jth layer. To prevent back diffusion in the reservoir layers the diffusion coefficients were divided arbitrarily by a factor 103. The corresponding kinetics are shown in Figure 12, with their parameters listed in the section “conservative scenario” of Table 6. The diffusion coefficients towards the food are overestimated by a factor 10. At intermediate Fourier numbers below 0.4, the kinetics is not significantly overestimated, but a significant conservatism is achieved at larger Fourier numbers when the overall migration is controlled by the second and the third layers as sources. This case study demonstrates how migration scenarios can be finely tuned to decrease the uncertainty related to the behavior of internal layers. The contact layer as a source can always be considered as a single monolayer.

Figure 12. Illustration of the conservative scenario of Table 6 based on the overestimation of the contribution of each source. The reference corresponds to the initial case-study configuration also depicted in Figure 11.

In practice, any uncertainty on the internal partitioning between layer can be converted into a conservative scenario by forcing mass transfer to the food and by relocating “artificially” the content from the layer to layer . The iterative procedure is illustrated in Figure 13 and can be applied iteratively to decrease a -layer problem into a , , etc. layer problem, until to reach tier 1 (total migration). The first iteration applied to the case-study is denoted “worst-case” scenario in Table 6. The procedure may overestimate dramatically the real migration, but it keeps the applicability of conservative calculations to demonstrate safety at low cost. For risk assessment, the procedure may be applied with caution as it may lead to unrealistic consumer exposure.

Figure 13. Principles of the simplification of a -layer problem (here ) into a problem with a lower number of layers and, therefore, easier parameterization. The represented distributions in the packaging corresponds to initial conditions at various tiers.

4.2.4 Strategies and equations to simulate multiple steps and conditions

This part discusses the invariance of migration estimates, namely , with the order of contact and thermodynamical conditions met by the components of the packaging before and during food contact.

Highlights on the strategies to simulate multiple steps and variable conditions.

- The initial dispersion of the substances between materials and the subsequent migration into the contact phase requires at least a two-step modeling and simulation.

- Temperature and relative humidity are variable during storage, transportation, etc. and subjected to uncontrolled diurnal and seasonal variations. Their variations can be integrated in chained simulations (one condition = one step), where the outputs calculated at the previous step are used as inputs at the next steps.

- Chained scenarios can be factorized under certain conditions in a shorter series of conditions without respecting the original order of steps or variations.

- Factorization keeps unchanged migration results only if the contact conditions are unchanged and if apparent partition coefficients are independent of temperature.

- Factorization should be avoided if the dispersion in food plays a significant role and in the presence of polar migrants.

- Factorized scenarios offer practical estimates for repeated uses.

- Probabilistic migration modeling (see §7) can be used to analyze the effects of known and unknown variations.

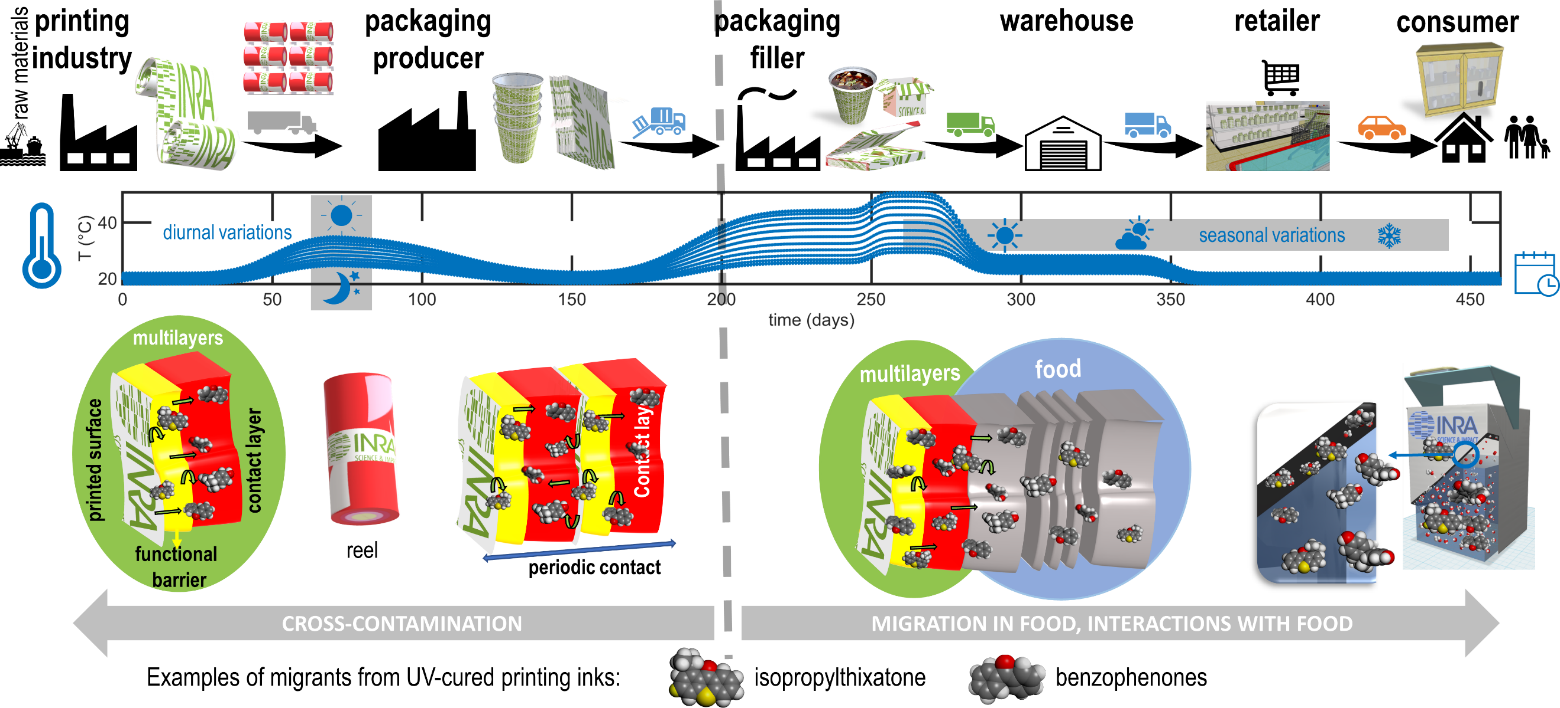

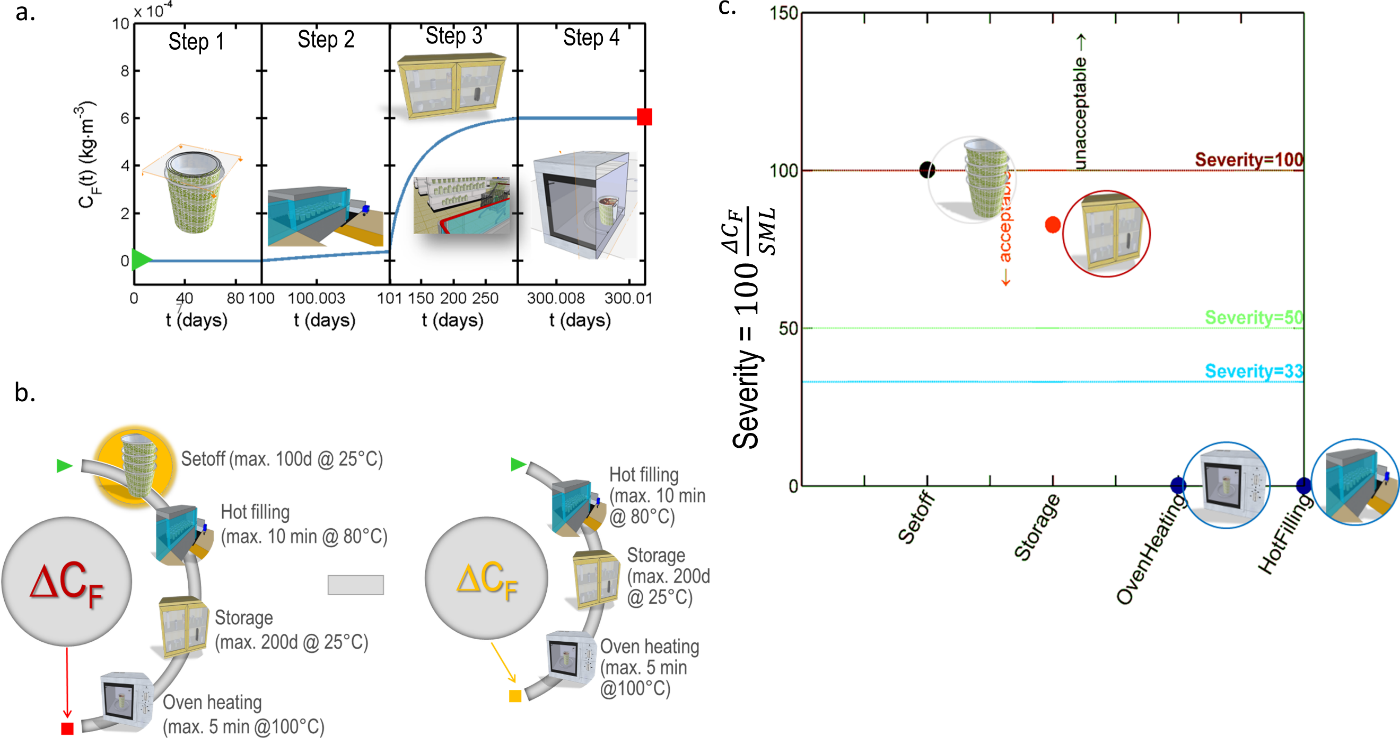

4.2.4.1 Problem formulation

Mass transfer between components and materials occur insidiously along the supply chain. Figure 14 illustrates conditions triggering or altering migration from printed materials. Many uncontrolled factors may affect the extent of mass transfer: i) variable contact or exposure times, ii) random combinations of storage and transportation steps for intermediate, finished packaging materials and packaged foods, iii) changes in temperature and relative humidity (e.g., seasonal, diurnal, international transportation), iv) modifications of boundary conditions during any stage of materials lifetime and product shelf-life. The redistribution of migrants between materials, layers, and components deserve special attention as it remains usually ignored by end-users. In practice, cross-contamination occurrences can be also considered indirectly (i.e., without causaility) as impurities and non-intentionally added substances. Without being exhaustive, cross-contamination is highly likely from cured adhesives and printing inks, from recycled materials and any material with rich volatile organic compounds. Packaging and materials stored in stacks and reels ease cross contaminations by contacting internal and external layers, regardless the presence of a functional barrier (absolute such as a metallic layer or relative such as barrier polymer) in the structure. Due to periodic conditions, the inner layer can act as a reservoir of contaminants before the food is put in contact.

Figure 14. Illustration of the redistribution of the migrants from UV-cured printing ink and their subsequent migration in food for long shelf-life products. The depicted cases cover hot-filled products (e.g., soups, pasteurized juices, sterilized dairy products), dry or ready-to-eat products stored in cardboard boxes.

From a mathematical point, the succession of steps and temperature variations can be seen as a sequence of constant conditions occurring in variable order. In the presence of conditions occurring at the time , the composite solution is obtained by integrating the coupled system via the Chasles’ relation:

The determinations of the duration of each step and their corresponding temperatures are critical. Representing all diurnal and seasonal temperature variations shown on the timeline of Figure 14 would require 2×450=900 successive simulations (one every 12 hours). On the one hand, a rigorous approach suggests that the congruence of all the steps should be strictly preserved to get reliable conclusions. In this case, how to identify the worst-case combination of conditions or steps? If the temperature variations are uncontrolled, how to build a conservative sequence? On the other hand, a naïve approach would suggest that the times series in Eq. XXX could be built from mutually independent steps assembled as the sum of a series of standard and well-controlled steps (e.g., cold, moderate and warm days), and one series and of stochastic contributions, representing an extra safety margin.

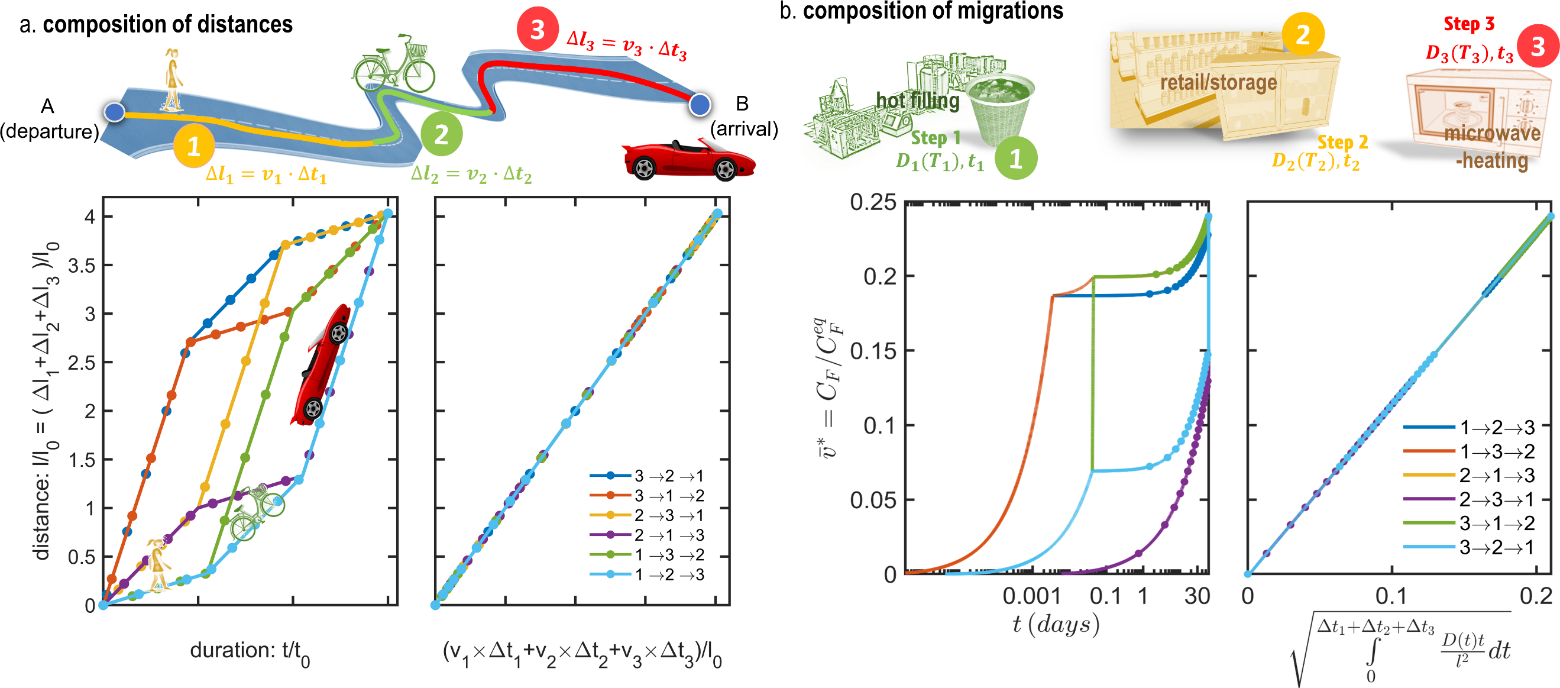

4.2.4.2 A first intuitive approach

The variations of between steps are not factorizable but the dimensionless times are. Their effects are additive and commutative (see Eq. XXX for the demonstration). If the diffusion coefficient is the only quantity varying with temperature and the plasticizer content (i.e., no change in the partitioning, and the packaging dimensions), the effects of is captured via the generalized Fourier number:

where is the diffusion coefficient of the most limiting material, component or layer, and the one-dimensional equivalent thickness (see Eq. to identify ).

Eq. XXX is equivalent to the low of the composition of velocities along a curvilinear coordinate system tangent to the trajectory going from A ( ) to B (). The analogy between spatial translation along a winding road and the translation along the curve vs. is illustrated in Figure 15 by comparing the travel via three modes of transport (each of duration at a speed: ) with the cumulated contamination after three steps (of duration at temperature . The total distance is , and the cumulated migration is independently on the order of the steps. Replacing the physical time by a cumulant measuring the total arc-length of the curve or the road makes it possible to use endpoint estimates (one simulation) instead of chained simulations ( simulations). In this new space, the residence times – represented by the density of markers on the curves – are not uniform. They are distributed more densely at departure and destination, but more sparsely in the middle region has the studied system follows different routes.

Figure 15. Illustration of the composition rules (a) for distances and (b) for the migration from a monolayer material, and of their invariance with the order of the steps (see Eqs. and ).

Eq. XXX suffers, however, a lack of generality as it applies only to the limiting mass transfer resistance and not to all layers. As a rule of thumb, It offers an acceptable if the function is monotone with (i.e., when . A simple counter-example can be, however, constructed by noticing that the concentration at equilibrium depends only on the initial and final states, but not on intermediate steps.

The conditions of exchangeability of steps (which is more generic than Eq. ) is discussed hereafter in more general terms. Two conditions are analyzed: i) when the effect of the mass transfer resistance is considered (explicit representation) and when the number of molecules does not change, and ii) when an implicit food representation is used (i.e., Eqs. XXX,XXX and XXX). The distinction between explicit and implicit food representation is relevant, as the boundary layer delays the effects of perturbations and may contain a significant amount of contaminants, which are ignored at low values in implicit representations (see §4.2.1.3).

4.2.4.3 Strict conditions of exchangeability with explicit food models

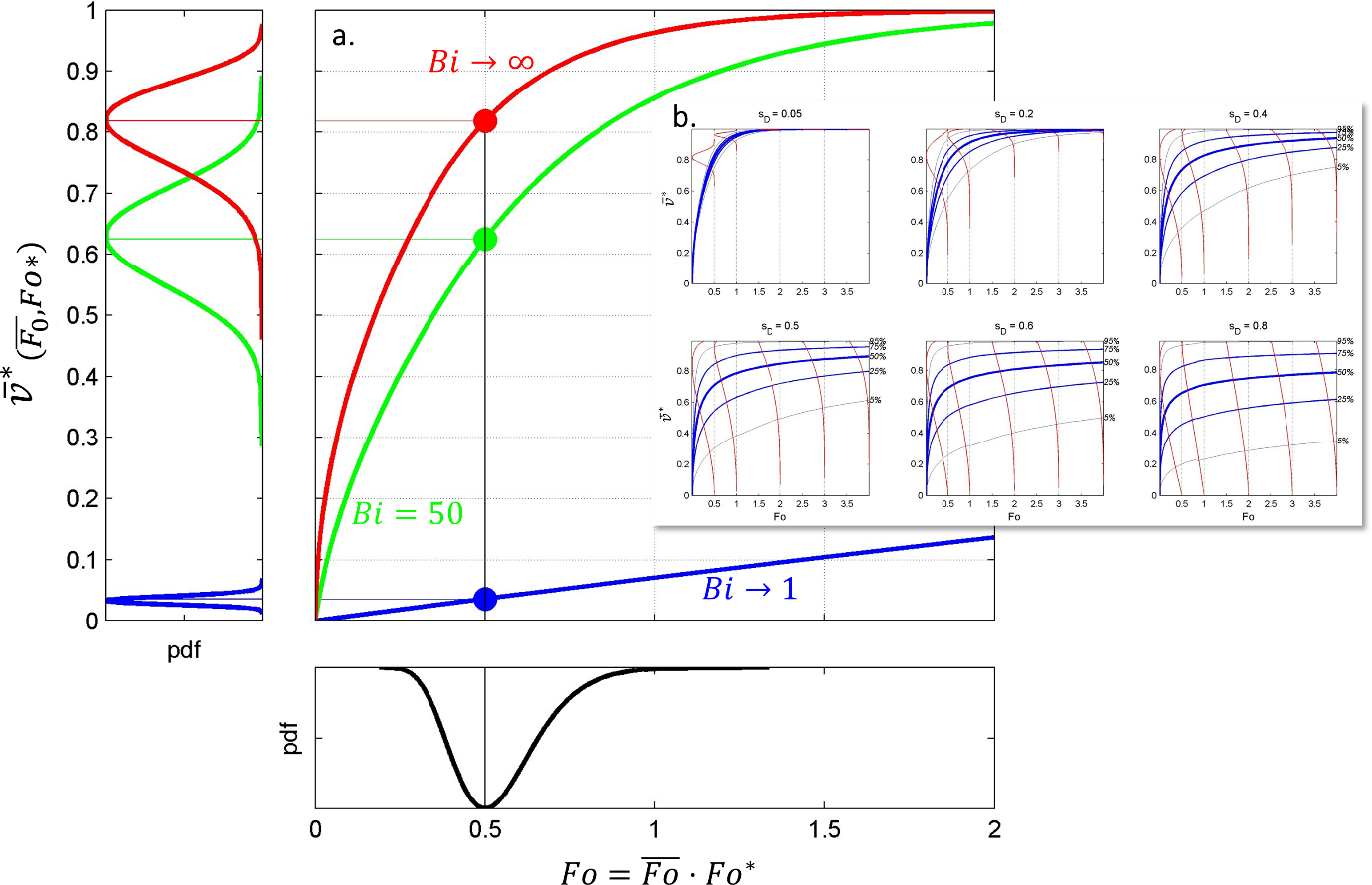

Microscopic description of the random walk of molecules between P and F